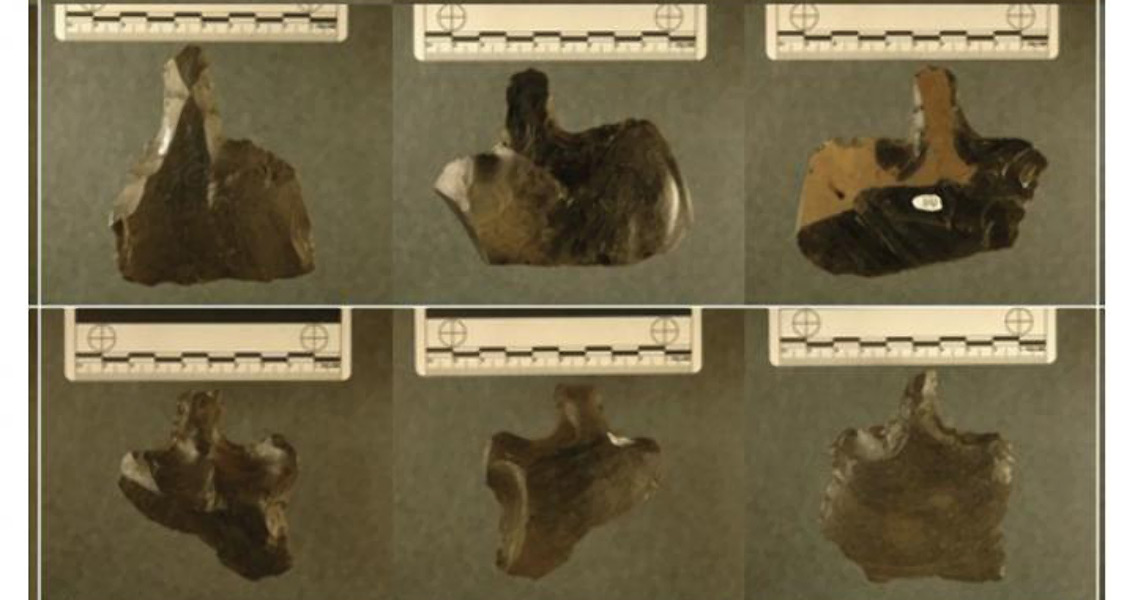

<![CDATA[The ancient inhabitants of Easter Island were not wiped out by war, according to a new study published in the journal Antiquity. Famed for its impressive yet mysterious stone head statues, Easter Island, and the fate of the inhabitants who constructed the monolithic Mo’ai heads, has long captured the imagination. Multiple interpretations exist for the disappearance of the Rapa Nui, the small Polynesian civilisation that inhabited the isolated island off the coast of Chile. A popular hypothesis is that they were victims of their own expansion. Believing that the first inhabitants reached the island by canoe around 800 CE, the explanation goes that the small initial settlement rapidly grew into a population of several thousand. When Captain Cook first set foot on the 63 square mile island in 1774, only 700 Rapa Nui remained The hypothesis claims that the Rapa Nui’s slash and burn form of agriculture saw them permanently alter the once densely forested island, essentially driving themselves extinct. As the Rapa Nui population expanded, the forests of the island were wiped out. Deforestation meant the inhabitants had no wood to build boats, leaving them unable to launch deep sea fishing missions for food. Perhaps more terrifyingly, it also left them with no way to escape the isolated island. Leading on from this, the hypothesis claims that war broke out between the islanders as competition for resources became deadly. A key piece of evidence to support this theory is thousands of obsidian triangles found on the island’s coast, known as mata’a. The abundance of the objects, and their sharpness, has lead many archaeologists to conclude that they were weapons of war, evidence of the Rapa Nui’s violent demise. The new study has dramatically brought this interpretation into question, however. Led by Carl Lipo, anthropology professor at Binghamton University, a team of researchers have concluded that the triangular objects were not weapons, but general purpose tools instead. “We found that when you look at the shape of these things, they just don’t look like weapons at all,” said Lipo in a press release from Binghamton University. “When you can compare them to European weapons or weapons found anywhere around the world when there are actually objects used for warfare, they’re very systematic in their shape. They have to do their job really well. Not doing well is risking death.” Lipo’s team used morphometrics to analyse the shape variability of a photo set of some 400 mata’a collected from the island, allowing them to study the shapes in a quantitative manner. Both the variability in the shapes, and their differences from other weapons, led Lipo’s team to conclude the obsidian objects were unlikely to have been used for warfare. “You can always use something as a spear. Anything that you have can be a weapon. But under the conditions of warfare, weapons are going to have performance characteristics. And they’re going to be very carefully fashioned for that purpose because it matters…You would cut somebody {with a mata’a], but they certainly wouldn’t be lethal in any way.” Lipo said. The traditional interpretation of the Rapa Nui is that it was a failed society, one which brought about it’s own demise. The new findings however, pull this theory into doubt, and raise a host of new questions about the fate of the people who built the remarkable Easter Island Heads. Lipo and his team believe that the collapsed civilisation narrative is just a later European reading of the record, rather than an actual archaeological event. “What people traditionally think about the island being this island of catastrophe and collapse just isn’t true in a pre-historic sense. Populations were successful and lived sustainably on the island up until European contact.” For more information: www.journals.cambridge.org Image courtesy of Carl Lipo, Binghamton University]]>

Easter Island Inhabitants Weren't Wiped Out By War