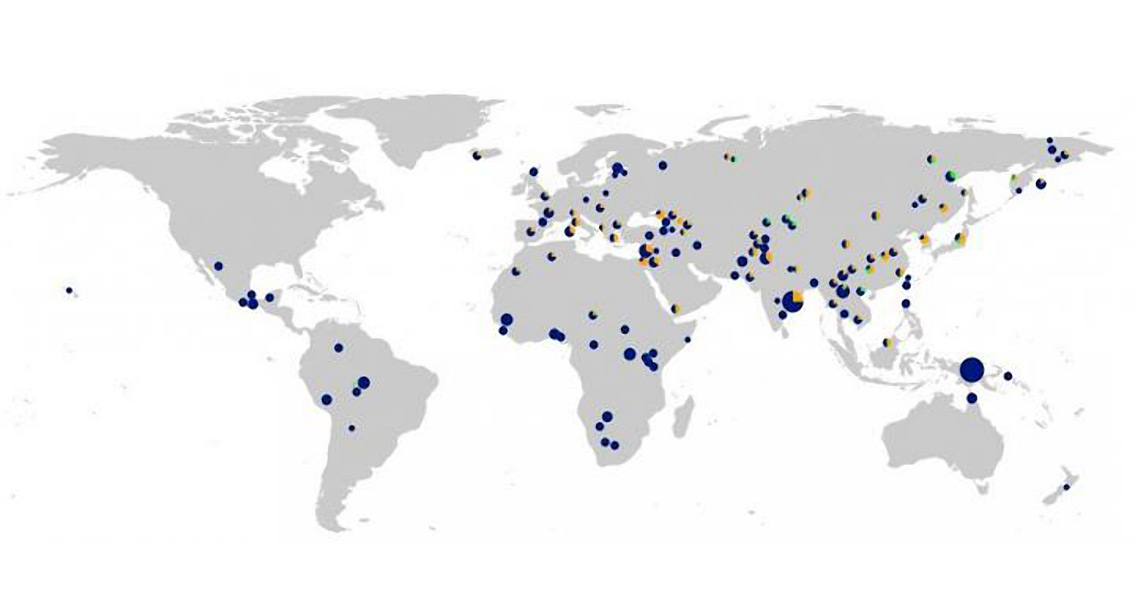

<![CDATA[A pair of new, independent research studies into the way Neanderthals influenced modern human DNA have revealed that the legacy of interbreeding includes not just allergies but also strengthened immune responses as well. Neanderthals and Homo sapiens co-existed thousands of years in the past, especially in regions such as Europe. Both species were genetically compatible, and interbreeding between the two species provided enough genetic variation in modern humans – the ultimate evolutionary winner – to provide several innate immunity genes, according to researchers from Leipzig, Germany’s Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology and Paris, France’s National Center for Scientific Research and the Institut Pasteur. Studies conducted in the past have revealed that anywhere from one percent to six percent of genomes of those of Eurasian descent are from Neanderthal or other ancient hominins. The two new independent studies focused on how functionally important this genetic heritage is in the form of three specific Toll-like receptor genes that respond to parasitic, fungal, and bacterial infections on the skin by triggering anti-microbial and inflammatory responses. The three genes in question, TLR 1, TLR 6, and TLR 10, were discovered to have the highest amount of Neanderthal ancestry in both European and Asian people after one of the two studies cross-referenced modern genetic samples with those recovered from ancient remains. Meanwhile, the second study was not concerned with immunity studies but instead in developing a broader understanding of the functional importance of genes passed down by ancient human ancestors. This second set of researchers pinpointed the three TLR genes as well, with the addition of discovering that the three ancient hominin genes offered selective advantages by being much more reactive to pathogens. The researchers pointed out that while those which were more highly sensitive could have served as a safeguard against infection, this higher sensitivity might have also paved the way for certain modern individuals to have allergic reactions to foods and environmental conditions, while others might not have the same levels of susceptibility. Researchers on the second study pointed out that higher sensitivity being linked to Neanderthal DNA makes logical sense, as the ancient hominid species had been present for around 200,000 years prior to modern humans arriving in Western Asia and Europe. This makes it much more likely for Neanderthals to have had higher levels of adaptation to local pathogens, food, and climate. Modern humans benefit from this higher level of adaptation thanks to prehistoric interbreeding with Neanderthals. The research articles, both of which were published in the American Journal of Human Genetics, are available here and here Image courtesy of Dannemann et al./American Journal of Human Genetics 2016]]>

Neanderthal DNA Gave Us Allergies, Immunities