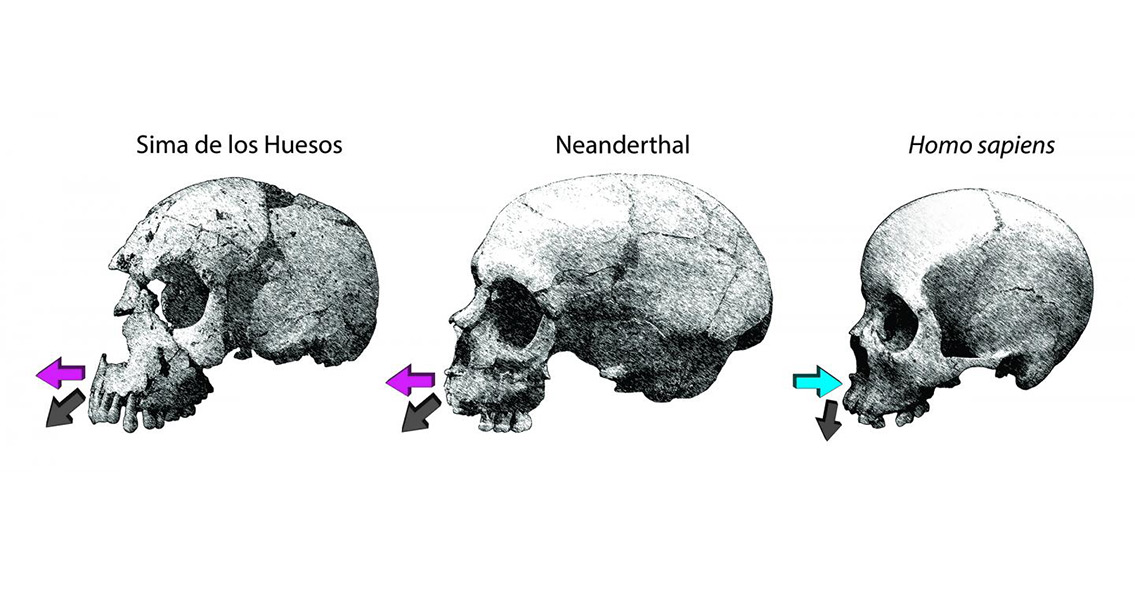

<![CDATA[Differences in the way Neanderthal and human faces grow and develop have been mapped for the first time. The research, carried out by an international group of scientists, adds vital new information to the long standing debate about how Neanderthals are distinguished from humans (Homo sapiens). Whereas Neanderthals had large, projecting (prognathic) faces which were similar to many of their ancestors, modern humans have a retracted face. The researchers have determined that a key cause is marked differences in the two species' post-natal growth processes. Morphogenic differences were evident by five years of age according to the study, published in the journal Nature Communications. Rodrigo Lacruz, PhD, assistant professor in the Department of Basic Science and Craniofacial Biology at New York University's College of Dentistry and leader of the international research team responsible for the study, explained the findings' significance in the broader understanding of the evolution of the Homo family tree. "This is an important piece of the puzzle of evolution," the paleaoanthropologist and enamel biologist announced in a press release. "Some have thought that Neanderthals and humans should not be considered distinct branches of the human family tree. However, our findings, based upon facial growth patterns, indicate they are indeed sufficiently distinct from one another." Two main cells are responsible for bone formation: osteoblasts which form and deposit bone, and osteoclasts which trigger resorption by breaking down bone cells. For their study, the team used an electron microscope and a portable confocal microscope to map the cell formation process that had taken place on the outermost layer of the skull of young Neanderthals, focusing on the upper jaw. Two skulls were used as the basis of the study, The Devil's Tower Neanderthal whose death is estimated at 4.6 years of age based on microanatomical enamel features, and the La Quina 18 individual estimated to be 6 to 9 years old based on human dental dating standards. These were the only two Neanderthals available to the team with facial bone surfaces intact enough to be mapped. Alongside the two Neanderthal children, four middle Pleistocene hominins were also studied by the team. The fossils from the Sima de los Huesos in north-central Spain are considered likely ancestors of Neanderthals based on DNA and anatomic analysis. Lacruz's team concluded that Neanderthals and other ancient hominins developed projecting upper jaw bones due to extensive osteoblast deposits on their faces without counterbalancing osteoclasts. Conversely, the growth of human faces is counterbalanced by resorptive osteoclasts in the lower part of the face, meaning the development of a less prominent jaw. Put simply, humans' retracted faces are a consequence of the outermost layer of the face containing large resorptive fields. For Neanderthal skulls the opposite is true, the prognathic faces are a consequence of large depositing fields on the outermost layer. As the study states, "Our results show that Neanderthals and SH hominins show extensive bone deposition over the maxilla (upper jawbone), a process associated with midfacial prognathism. This is different from the resorption that dominates over the retracted human maxilla. Thus, the faces of modern humans are distinct from those of the Neanderthal and SH fossils in that the growth processes, as evidenced by anterior maxillary remodeling activity state, differ markedly during the postnatal period." The study's results suggest that Neanderthals shared a similar facial growth pattern to earlier hominins. This raises the question as to when the bone development process seen in human faces arose, a question Lacruz and his team hope to answer with their next study. For more information: www.nature.com Image courtesy of Rodrigo S Lacruz]]>

Neanderthal and Human Facial Growth Differences Revealed