<![CDATA[Thanks to the results of a new international research study, the time frame for the birth of the Himalayas has been narrowed down significantly with the discovery of the Indian Ocean’s first oceanic microplate, created by the collision between Eurasia and India on a tectonic level. There are a minimum of seven known microplates in the Pacific. However, this is the first of its kind to be discovered in the Indian Ocean, with its discovery facilitated by satellite radar imaging. The new data has aided in completing the jigsaw-like puzzle that is the Earth’s tectonic plate system, and has also helped provide a clearer idea of when India and Eurasia collided to form the Himalayas – information that has proven to be elusive through decades of research. The team of scientists from both the United States and Australia have analyzed the data, announcing that, based on their findings, this collision occurred roughly 47 million years in the past. Indications to that effect were supported by the discovery that the Antarctic Plate, while nowhere near the collision zone, caused a fragment to break off in the center of the Indian Ocean. This microplate, roughly the size of Tasmania, has been named the Mammerickx Microplate in honor of seafloor mapping pioneer Dr. Jacqueline Mammerickx, according to a joint press release published by the international team. The researchers revealed that the rotation of the Mammerickx Microplate was discernible from the pattern of hills and grooves left in the ocean floor’s topography that turned the underwater landscape into a jagged and broken one. The crustal stress left behind by the birth of the Himalayas was a strong indication of the date of the collision. Both the Indian and the Eurasian plates are still grinding against one another as they continue to collide, resulting in a number of earthquakes on an annual basis as tectonic pressure builds and releases. However, at the time of the Himalaya forming collision, the Indian subcontinent was moving at a remarkably swift 15 centimeters every year. This doesn’t seem very fast, but is close to the maximum speed that tectonic plates are capable of traveling – and was likely a major contributor to the splintering of the Antarctic plate and the creation of the Mammerickx Microplate at the time of collision. The research study that reveals the team’s findings was led by a pair of scientists from the University of Sydney, Professor Dietmar Müller and Dr Kara Matthews, as well as a researcher from San Diego’s Scripps Institution of Oceanography, Professor David Sandwell. Dr. Matthews explained that finally pinpointing the date of the largest known continental collision in the geological history of the Earth has specific benefits in understanding how mountain belt growth may play a part in occurrences of major climate change. For more information: www.sciencedirect.com]]>

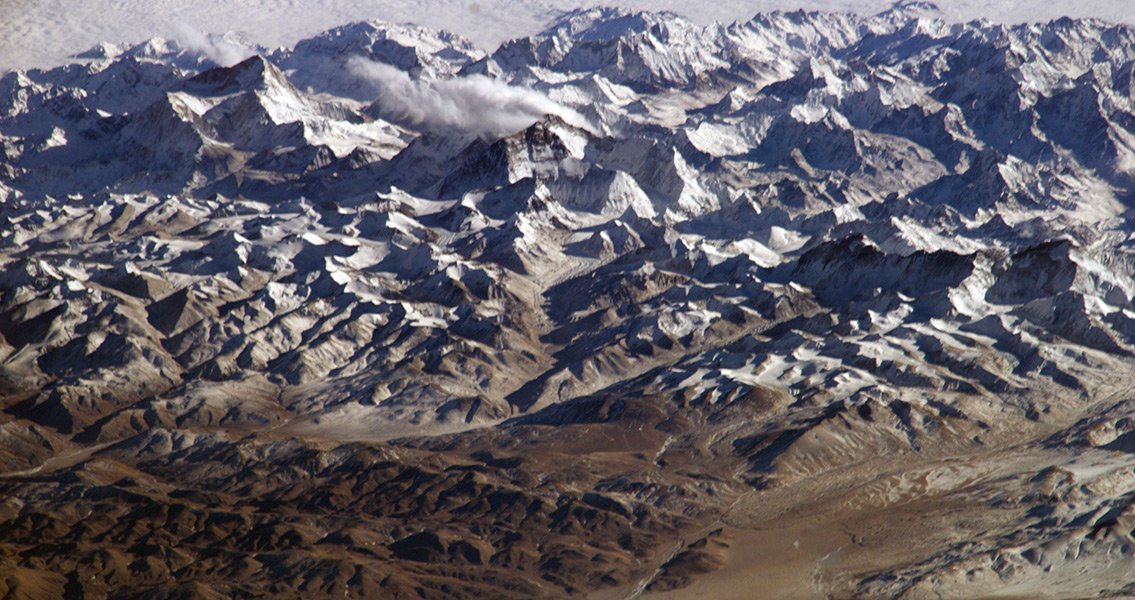

Timeframe for Birth of Himalayas Narrowed Down