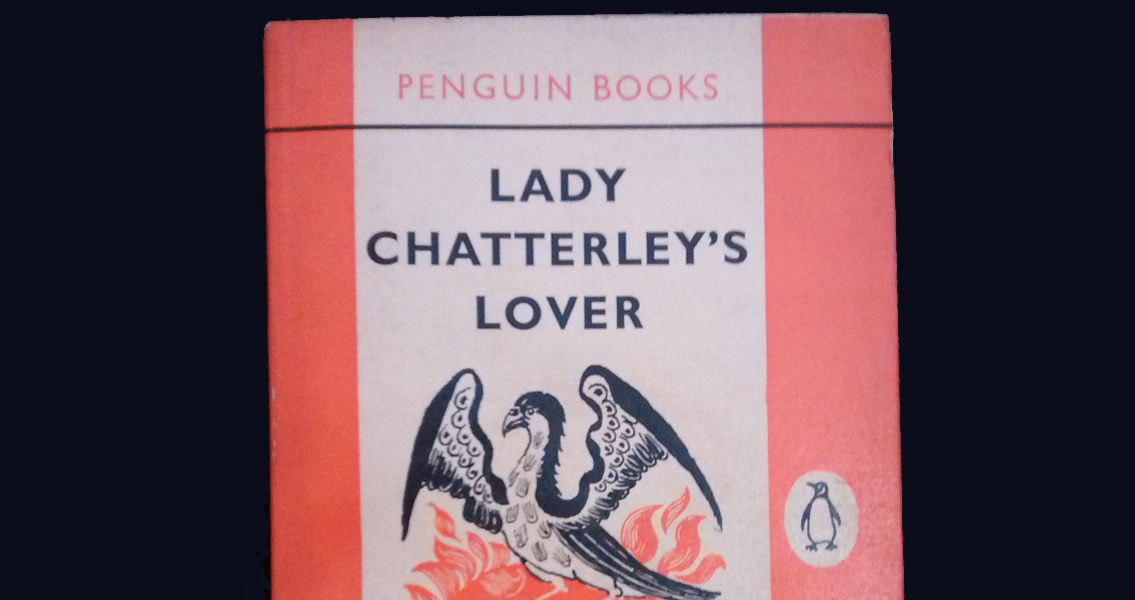

<![CDATA[The landmark obscenity case against Penguin Books for publishing an unexpurgated edition of D.H. Lawrence's 'Lady Chatterley's Lover' drew to a close on 2nd November, 1960. Hugely significant for both the world of literature, and British culture in general, the acquittal of Penguin Books seemed to represent a growing cultural liberalism in the United Kingdom at the start of the 1960s. Penguin's trial served as a test case for a recently created piece of legislation, the Obscene Publications Act. Passed in 1959, at around the time the publisher laid plans to release a new collection of D.H. Lawrence's works, the Obscene Publications Act was created to clear ambiguity between publications which were pornographic, and those deemed to have literary merit. Significantly, the Act was vague when it came to clarifying who could be called as a witness in obscenity cases. This made it possible for Penguin's defence to call a variety of experts, including renowned writers and academics, to testify to the work's literary value. Equally crucial, unlike previous obscenity legislation, the 1959 Act specified that a work had to be judged as a whole. Simply highlighting certain controversial passages was not enough to prove the whole piece was worthy of censorship. Lawrence himself had died thirty years before the trial took place. Lady Chatterley's Lover, his final novel, was published in Florence in 1928, and Paris the following year. In 1932 an expurgated edition was released in England, with a full, uncensored release getting published in New York in 1959. The novel tells the story of Connie Reid, an upper middle class bohemian introduced to sexual liaisons while still a teenager. Aged 23 she marries Clifford Chatterley, who is later paralysed while fighting in the First World War. Upon his return, Clifford becomes a successful writer, a situation which results in the Chatterley household becoming a centre for writers and intellectuals. Increasingly frustrated by her husband's detachment and loss of sexuality, and what she sees as the lack of sensuality in the intellectuals that frequent the household, Lady Chatterley embarks on a passionate affair with Oliver Mellors, the family's gamekeeper. A scandal erupts when Clifford Chatterley and Oliver's wife find out about the affair. At the novel's end, both Connie and Oliver live apart and frustrated, hoping that their respective spouses will sanction the divorces they need to continue their sensual affair. Lawrence's novel is generally interpreted as a glorification of pure, unadulterated sensuality in the post war, industrialised world which had seen humanity become so dehumanised. For those who objected to its publication, the problem lay in the unrestrained honesty with which it portrayed sexuality. By the end of the 1960 trial Penguin's lawyer, Michael Rubenstein, had secured a host of testimonies to confirm the book's literary merit, including members of the clergy alongside respected literary figures. They managed to convince the jury that Lady Chatterley's Lover was not a work of pornography, and Penguin Books were acquitted. Coming at the start of the 1960s, a decade associated with liberal attitudes, personal freedom and rebellion, the victory of Penguin seems a particularly symbolic moment in hindsight. As an editorial in the Guardian shortly after the trial revealed, the verdict seemed to reflect a growing willingness to challenge the old-fashioned, conservative values of those in society who failed to appreciate the changing times. "Fort Sex is the last stronghold of taboo in our society, and already the outer fortifications are starting to give way before the assault, and then there won’t be any more taboo subjects left. Or will there? I have a horrible suspicion that people may insist on keeping one area permanently shrouded, shifting the subject as their feelings dictate." Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons user: Twospoonfuls]]>

Lady Chatterley's Lover Deemed Not Pornographic