<![CDATA[This week marks the anniversary of the killer smog which struck the town of Donora, Pennsylvania, between 26th and 31st October, 1948. Highlighting the dangers of reckless industrialisation, the Donora Smog Disaster remains one of the worst pollution caused catastrophes in the history of the United States. The tragedy was crucial in kick-starting the legislative drive which eventually culminated in the USA's Clean Air Act. In 2012, a Donora resident, Charles Stacey, described the effects of the smog in an NPR interview. "The smog created a burning sensation in your throat and eyes and nose, but we still thought that was just normal for Donora". Situated around forty miles from Pittsburgh, in 1948 Donara was a small, industrial town with a population of around 14,000 people. Home to steel mills and zinc works which employed much of the local community, smog frequently descended on the town in the mornings, although it typically dissipated within a few hours. This perhaps explains why its population was slow to realise the severity of the situation they found themselves in on the morning of 26th October. A specific meteorological phenomena, known as thermal inversion, caused the thick blanket of smog to remain over the small town. The unusual condition occurs when a layer of warm air settles over a layer of cooler air close to the ground. As a result, the cooler air is pressed to the ground, and airborne pollutants are prevented from rising and scattering. In Donora, this meant a thick, toxic mix of nitrogen dioxide, fluorine and sulphuric acid was stored in a smog over the town. It darkened the days, at times making it impossible to see objects just a few feet away, and, as Stacey's testimony shows, quickly started to cause breathing problems for the local population. For the elderly or people with existing respiratory conditions, the effects were tragic. Between 30th and 31st October nineteen people were killed as a result of the pollution in the air. All of the fatalities were aged between 52 and 85 years of age. 500 local residents were also hospitalised, again, due to respiratory problems. The sources of the pollution were clear. The Donora Zinc Works was well known to locals as a major polluter, in the 1920s its owner had been forced to compensate the community for damages caused by pollution from the plant. Shortly after the Donora Smog incident local resident Lois Bainbridge wrote to the local Governor claiming that people in the area had complained for years about air pollution which stripped the paint from the walls of their houses, and stopped fish living in the local river. This was a time of little regulation concerning air pollution. In the period following the Great Depression and the Second World War, environmentalism and sustainability were issues far from people's minds, particularly so in towns such as Donora where the main employers of the local population were also the main polluters. After the disaster at Donora, the beginnings of a campaign for change started in the United States, as the very real dangers of air pollution became apparent. Nationwide coverage of the tragedy led to an environmentalist campaign for reform. In 1955, the Air Pollution Control Act was passed, providing a substantial budget to launch research into the effects of air pollution. In 1963 came the Clean Air Act, which, through substantial later revisions, would provide comprehensive legislation to police air pollutants in the United States. Sixty-seven years after the killer smog descended on Donora, the disaster remains a potent reminder of the hazards associated with industrialisation.]]>

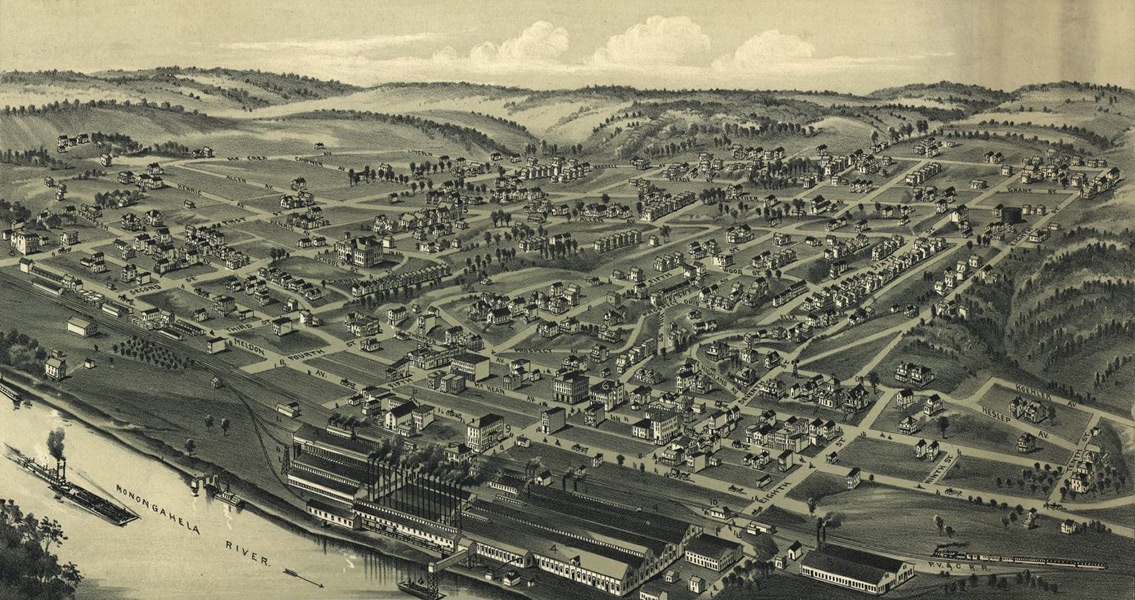

Killer Smog Looms Over Donora