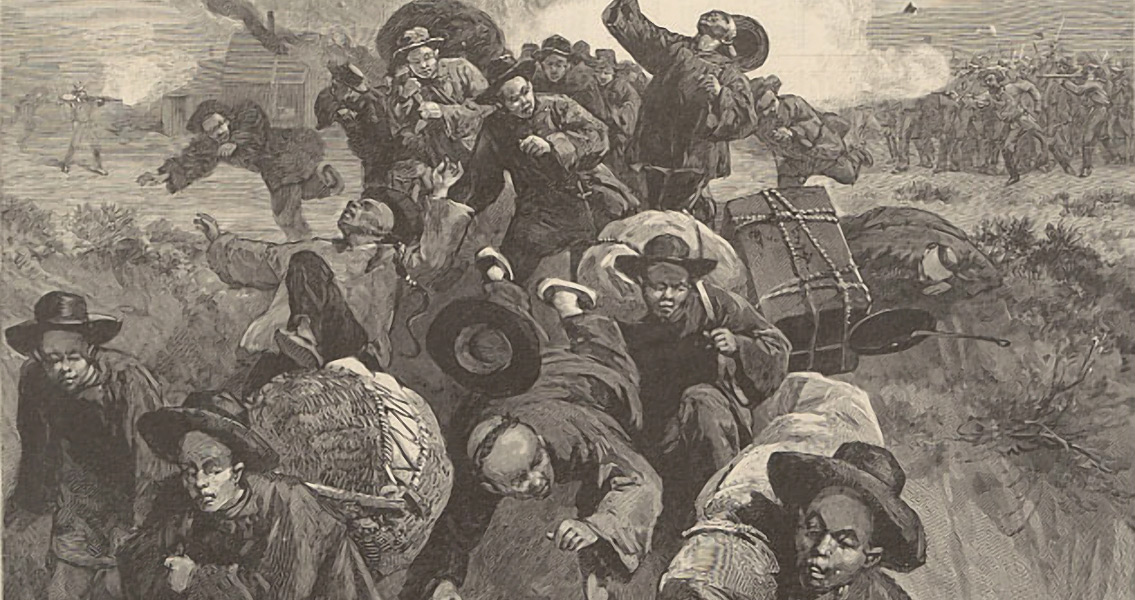

<![CDATA[The Rock Springs Massacre took place on 2nd September, 1885. That evening, twenty eight Chinese people were murdered, and the Rock Springs' Chinatown was burnt down in an explosion of rioting. Even when compared to the violence of America's Old West, the riot in Rock Springs, Wyoming was shocking in its intense brutality. It also highlighted a dangerous, long brewing racial tension between white and Chinese workers in the United States. At the heart of the Rock Springs Massacre was a coal mine owned by the Union Pacific Railroad, which employed 331 Chinese and 150 white workers. Tensions between workers of European origin and Chinese had been growing for some time in the Old West. Vigilante violence had driven Chinese workers out of mining and agricultural settlements around the region, with the authorities often reluctant to prevent acts of mob violence, or even occasionally participating in it themselves. In 1870, for instance, a street march by white residents in San Francisco saw them publicly declare that not only were Chinese workers not welcome in the United States, they should also not consider themselves safe. A year later, when a fight broke out between rival Chinese gangs in the city, white vigilantes intervened and murdered some twenty three Chinese people in the affected neighbourhood. Far from isolated instances, the 1870s and 1880s were full of explosions of violence between the two groups, culminating in 1882 with the US government placing restrictions on Chinese immigration to the country. Chinese workers had been flocking to the United States since the 1840s, eager to take jobs which offered wages roughly ten times higher than they could earn in China. One major consequence was a more competitive labour market, which undermined attempts by white workers to achieve collective bargaining. Union Pacific, as well as other major employers, often took on Chinese workers to replace strikers. Alongside broader xenophobia which existed in the community towards the increasing Chinese population, workers at the Rock Springs mine and elsewhere became increasingly resentful of this group who would work for lower wages and refused to strike. Increasing frustration saw more and more Scandinavian, Irish, English and Welsh immigrant workers sign up to a new nationwide union - The Knights of Labor. A strike in 1884 at the continued failure of the mine owners to increase wages proved the final straw, and the managers of the Rock Springs mines were told to exclusively hire Chinese workers. In this period of simmering tensions, a fight broke out on the 2nd September, 1885, in the Rock Springs mine. Two Chinese workers were attacked, one fatally the other badly wounded, by white workers. A foremen broke up the fighting, and the white workers left their jobs and went home. Gathering weapons such as guns, clubs and hatchets, they headed to the meeting hall of the Knights of Labor to discuss their next move. Gathering supporters from other local mines and the town's saloons, the miners headed for Rock Springs' Chinatown. Coinciding with a Chinese holiday, many of the Chinese workers had stayed at home and were unaware of the situation which was developing. As the mob descended on Chinatown, many Chinese managed to escape, but those who hadn't were brutally beaten as their homes were vandalised and torched. A week later, on 9th September, U.S. troops escorted the Chinese miners and their families back into the town where many of them eventually returned to work in the mine. Forty five of the white miners involved in the attack were fired by the Union Pacific, but no legal action was taken against anyone involved in the violence. Chinese diplomats successfully pressured the President into awarding $150,000 of damages to the Chinese miners affected by the Rock Springs Massacre. Nevertheless, for many staying in Wyoming seemed too risky, especially as Union Pacific threatened those who refused to return to work out of fear for their safety with dismissal. Over the following years Chinese miners and their families gradually left Wyoming, either returning to China or heading to safer areas of the USA. Highlighting the continued volatility of the situation, an encampment of federal troops was stationed near Chinatown for the next thirteen years, in an attempt to keep the peace.]]>

The Rock Springs Massacre