<![CDATA[US President Ronald Reagan began firing 11,359 air traffic controllers who were striking in violation of an order for them to return to work, on 5th August, 1981. The event is regarded as a landmark example of the strict domestic and economic policies of Reagan's administration. From his election campaign onward, Reagan had promised reductions in government spending, reductions in capital gains and incomes tax, reductions in government regulation, and reductions in inflation through strict controls on the money supply. Associated with these economic policies, and crucial for their successful implementation, was a domestic policy which took a firm position on trade unionism and strike action. Coming early in Reagan's first term as President of the United States, the air traffic controllers strike was an opportunity to make an important statement about his stance on unionisation. 13,000 Air-traffic controllers in the Professional Air Traffic Controllers Association (PATCO) had gone on strike on 3rd August, 1981, after negotiations with the federal government had failed to secure the pay rise and shortened work week they had demanded. The mass strike was extensive enough to almost cripple air travel in the United States, grounding 7,000 flights and leaving passengers stranded. With millions of Americans badly affected by the flight cancellations, Reagan ordered the air-traffic controllers to return to work within 48 hours or lose their jobs. A mark of the force with which the strikers would be dealt with was shown in the fate of Robert Poli, PATCO's president. On the day the strikes started he was found in contempt by a federal judge, and fined $1000 for each day of the strike. Reagan's actions were legal by US law. The air-traffic controllers were employees of the federal government, and thus banned from striking. In terms of precedent however, Reagan's actions were unusually harsh. Air traffic controllers and other unions representing federal employees had struck under previous presidents and had no action taken against them. On 5th August Reagan carried out his threat, and ordered the federal government to start firing the 11,359 strikers who had not returned to work. A life time ban was also placed on the controllers who had not returned to work within the deadline, meaning the Federal Aviation Authority (FAA) was prohibited from ever rehiring them (this ban was only lifted in 1993, during the presidency of Bill Clinton). PATCO lost its status as a recognised trade union, despite having supported Reagan during his presidential campaign. Undoubtedly Reagan's ruthless response made the statement he wanted. However, the move was also incredibly risky. The FAA was forced to rush recruit new staff, many of which lacked the experience of those who had been fired. Some of Reagan's advisers feared a major air disaster in the aftermath of the sackings, an event which would have been devastating to his credibility. As it was, it took the FAA ten years to return to the levels of staffing it had prior to the strike. The US government eventually spent more on replacing the strikers than it would have on accepting PATCO's demands. In the broader trend of American history Reagan's treatment of the strikers was a key turning point, the effects of which can still be felt today. Other politicians soon took Reagan's example in dealing with public sector unions. Reagan may have been responding to an illegal strike, but it saw a trend developing which saw public sector unions' ability to bargain in anyway diminish dramatically.]]>

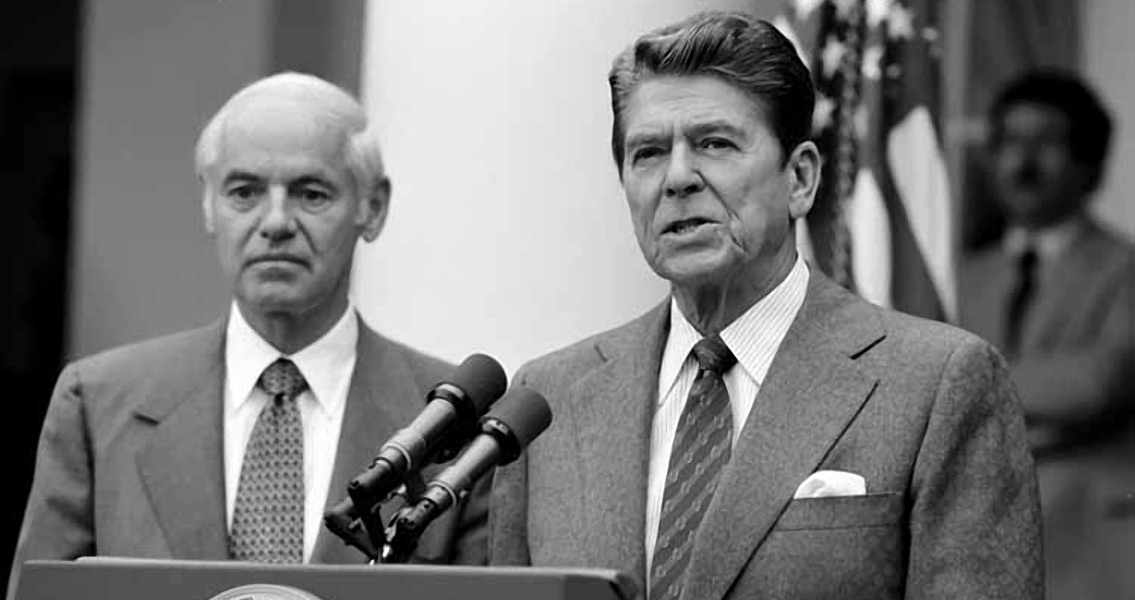

Reagan Starts Firing Air Traffic Controllers