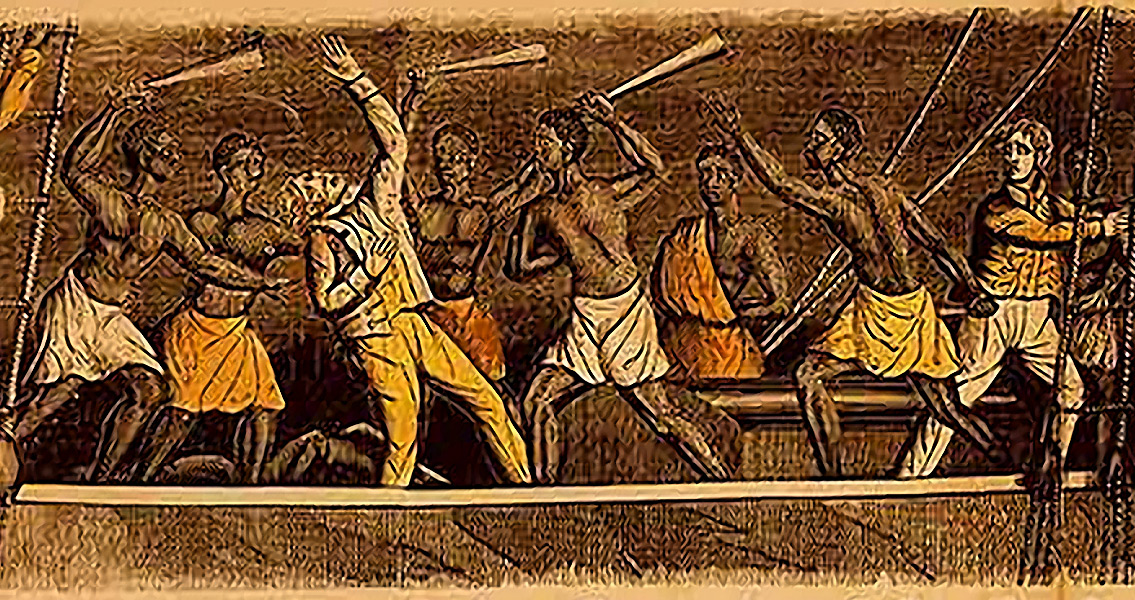

<![CDATA[At around 4:00am on 2nd July, 1839, Joseph Clinque led a slave mutiny on the Spanish schooner Amistad. The event became the basis for one of the most significant court cases in US history and a defining moment in the development of the abolition movement in the United States. Sometime in April 1839 Clinque, a 26 year old man from Mende in Sierra Leone, was captured alongside hundreds of others from the West African tribes by Spanish slave merchants. With his wife and three children still free and living in Sierra Leone, Clinque and 500 other slaves were taken, chained hand and foot, aboard the Portuguese slave vessel Teçora to the Caribbean. Teçora finished its voyage by entering Cuba under the cover of night. The secretive approach was because of Anglo-Spanish treaties which had made the trade of slaves from Africa a capital crime. Slavery was legal in Cuba however, meaning once smuggled ashore it would be possible to trade the slaves on the Cuban market. Highlighting the horrendous conditions endured by the captives aboard Teçora, a third of the slaves had died by the time the ship reached Havana. Clinque and 53 other slaves, including four children, were bought by two Spaniards: Jose Ruiz and Pedro Montes. The slaves were collected aboard the Amistad, a small schooner built in Baltimore especially for the slave trade. It set sail on a 300 mile journey to transport the slaves from Havana to Puerto Principe, on another part of Cuba. The mutiny started three days into the voyage. Clinque used a nail to pick the locks of his chains and free the other captives. The escapees, armed with machete like weapons they had found in the vessel’s stores, stormed the ship, killing the Amistad‘s captain and cook, and injuring Montes and Ruiz. The lives of the two Spaniards were spared for their navigational skills, and they were tasked with sailing the ship back to Africa. Montes and Ruiz deceived the captives and had the ship sail back and forth along the coast of the Americas. After two months at sea the vessel was spotted by the USS Washington off the coast of Long Island. The difficult voyage had seen around a dozen of the slaves perish. The US Navy ship escorted the Amistad to Connecticut, where Montes and Ruiz were freed and the Africans were imprisoned pending an investigation into the mutiny. Quickly the mutiny escalated into an international issue which engaged directly with the long standing controversies over slavery. A group of evangelists, led by Lewis Tappan, worked to publicise the incident as a means to expose the evils of the slave trade. A key turning point took place when they found two other men from Sierra Leone who could serve as translators for Clinque, allowing his side of the story to be publicised. Increasingly, abolitionists painted and spread a vivid depiction of the horrendous conditions endured by the slaves. They launched a case, arguing that the Africans had been enslaved illegally and had thus broken no laws in trying to escape from bondage. On the other side, Montes and Ruiz sued the slaves, on the basis that they had been deprived of their property. They demanded the return of the slaves, which they fraudulently claimed had been born in Cuba. The Spanish government was eager for the slaves to be returned to Cuba to stand trial for piracy and murder. Tremendous diplomatic pressure was therefore placed on US President Martin Van Buren to find a quick solution to the mutiny which would appease the Spanish demands. An interesting sub-plot to the case was the Spanish awareness that if Mortes and Ruiz were found guilty of having kidnapped the slaves from Africa, Spain’s infringement of the treaty banning the African slave trade would be revealed. This, in turn, would provide the British with justification to intervene in Cuba. An initial trial, in January 1840, ruled that the slaves had been imprisoned illegally. As such, they would not be forced to return to Cuba to stand trial but instead freed and returned to Africa. Shockingly, Van Buren and the Spanish government both intervened in the case, and appealed the verdict to the Supreme Court. In March 1841 the Supreme Court confirmed the original verdict, ruling again that the slaves had been imprisoned illegally. With financial assistance from the abolitionists that had backed their campaign, the Africans from the Amistad set sail for West Africa in November 1841. For the United States, the verdict of the trial was pivotal. It revealed the growing momentum of the abolition movement, and the growing contradictions between US law and the moral principles supposedly embodied in the country’s Declaration of Independence. The event became a public as well as political spectacle, highlighting the divisions between slave owners and abolitionists. The result set an important legal precedent concerning the importance of ‘natural law’ over the property rights of the slave owners and as such, the outcome of the Amistad trial was a crucial step in the process which ultimately culminated in the Thirteenth Amendment in 1865.]]>

The Amistad Mutiny