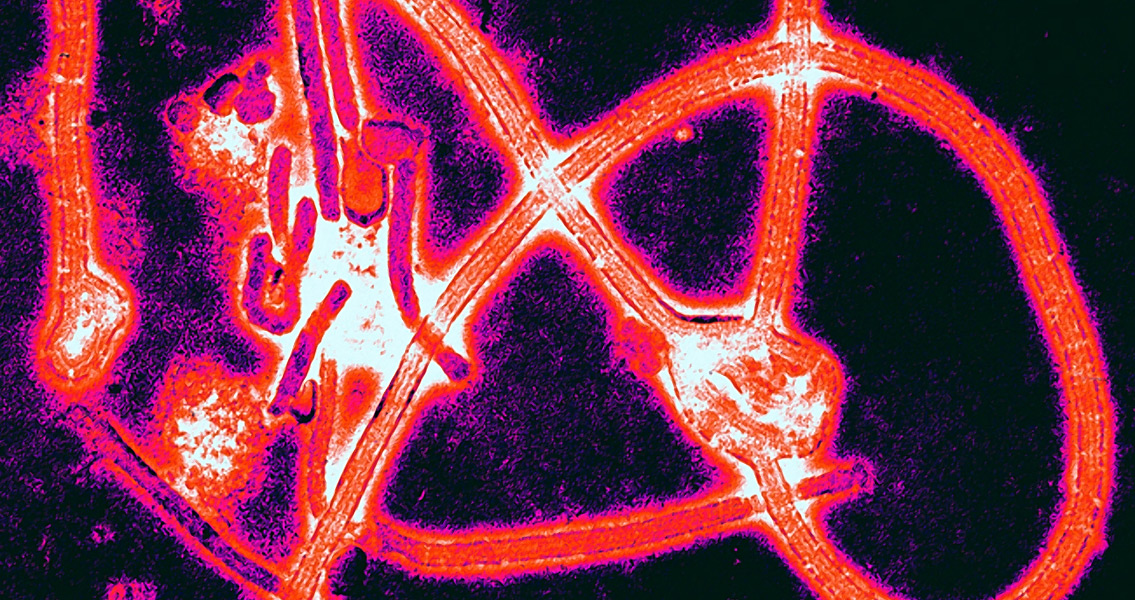

<![CDATA[A professor of history and infectious diseases from Michigan University has suggested in a new study that the Plague of Athens which began in 430 BCE and lasted for five years may have been the first recorded outbreak of Ebola. Earlier studies of rodents have established that the highly fatal virus was already present as long ago as 20 million years, and Powel Kazanjian proposes that the disease may have jumped species much earlier than officially accepted, Live Science reports. The first official record of an Ebola outbreak in humans is from 1976, when the disease struck the Democratic Republic of Congo. Yet the Plague of Athens, also called by scientists the Thucydides syndrome because the ancient historian himself contracted it and later recorded the events from the time, had pretty similar symptoms to the viral disease. These included headache, fever, fatigue, stomach pain and pains in the joints as well as severe vomiting, diarrhea, and reddening of the eyes. According to Thucydides, some of the affected also experienced coughs, rashes, seizure, and even loss of digits, perhaps due to tissue necrosis. The illness that struck ancient Greece also caused severe dehydration. Kazanjian is basing his suggestion not only on the similarity of symptoms, however. Based on Thucydides records, the Plague of Athens originated in sub-Saharan Africa, a region the ancient historian and his contemporaries called Aethiopia and also the region where modern outbreaks of Ebola have occurred, the researcher told Live Science. He believes the virus was spread by Africans who had traveled to Greece in search of employment as servants and farmers. In modern times, it has been established that two species of fruit bats native to sub-Saharan Africa are carriers of the disease and since bat soup is a delicacy in the region, there has been a suggestion that this is the way in which the zoonosis passed from the animals to people. The disease in Athens, Thucydides wrote, killed the sufferers within seven to nine days (as Ebola typically does), and only a minority survived. What’s more, physicians and those who attended to the sick were among the first to die, which is true of modern Ebola outbreaks, although this has also been true of other highly infectious diseases through the ages. One further parallel between the Plague of Athens and modern Ebola outbreaks is how fear aggravated the sufferers’ condition and also helped the spread of the disease as people crowded together. Kazanjian writes in his paper that Thucydides’ account of the period provides a historical perspective to how communities react to the outbreak today, often making it more difficult for medical personnel and volunteers to control the outbreak. The latest outbreak of the virus in Africa took 11,000 lives, according to figures from the World Health Organisation, out of around 27,000 people who contracted it. According to WHO records this was the largest Ebola outbreak in history. The Plague of Athens struck the city state during its war with Sparta, the Peloponnesian War, Ancient Origins notes, leading to the death of about a quarter of its population. The cause of the outbreak has been subject to much debate, with suggestions ranging from smallpox and typhus, to bubonic plague and anthrax. Kazanjian himself does not insist that his suggestion should end the debate, admitting the cause of the Plague of Athens “remains elusive.” For more information: “Ebola in Antiquity?” Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons user: Thomas W. Geisbert, Boston University School of Medicine]]>

Did Ebola First Strike In Ancient Greece?