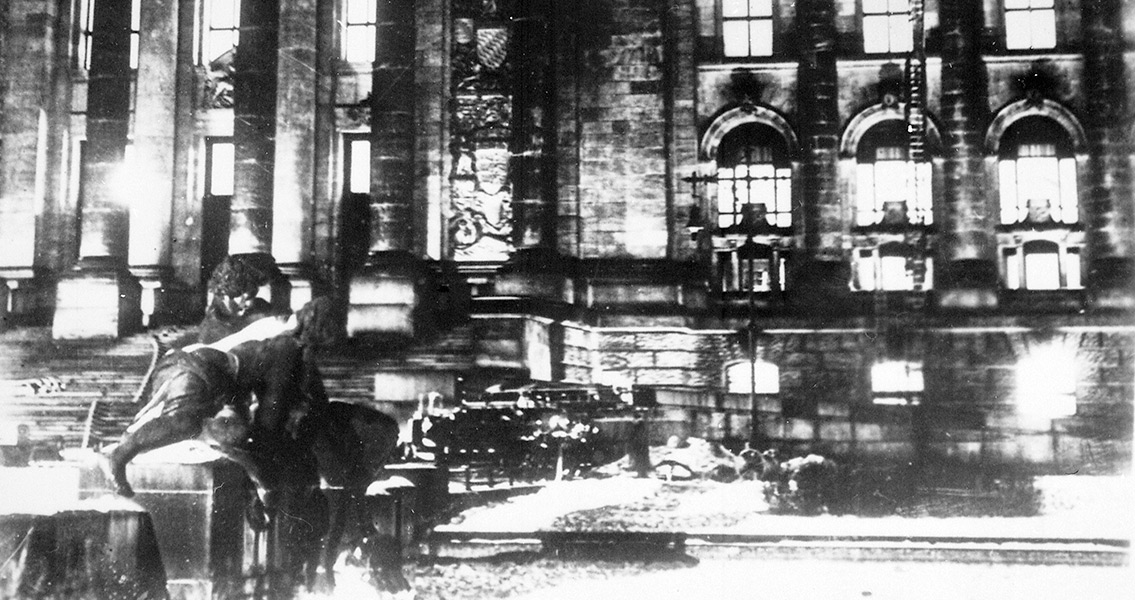

<![CDATA[On 27th February, 1933, the Reichstag Building in Berlin was engulfed in flames. Despite the best efforts of fire fighting crews, the Reichstag, the physical representation of German democracy, was gutted by the fire. After the fire had been put out, firemen and police conducted a search of the building. Along with unburned bundles of firelights, officials found Marinus van der Lubbe. Van der Lubbe, a young Dutch council Communist and recent arrival in Germany, declared that he had started the fire. Van der Lubbe and four Communist leaders were arrested for deliberately burning down the Reichstag. Following the blaze Adolf Hitler, who had been sworn in as Chancellor of Germany four weeks before, managed to pass an emergency decree suspending civil liberties. Mass arrests of Communists followed, including all of the Communist parliamentary delegates. The main opposition to the National Socialist German Workers' Party had been removed, enabling Hitler to consolidate his power. The Reichstag fire has received a huge amount of scholarly attention as it marks a key moment in German history. Historians have disagreed as to whether van der Lubbe acted alone to protest the condition of the German working class, as he himself claimed. It has been argued that the arson was planned and ordered by the Nazis as a false flag operation. New research has looked at how this consensus came about. Benjamin Carter Hett, Professor of History at City University of New York, has been exploring why the single-culprit narrative which blames Van der Lubbe has been widely adopted. "The long Reichstag fire controversy tells us important things about how we have written the history of Germany’s twentieth century," Hett writes in an article published recently in Central European History. “It tells us about the subterranean forces, especially of legal and political interest, that have shaped the master narrative; and it tells us about our attitudes toward different kinds of sources and authors.” Hett argues that the two conflicting arguments about who started the Reichstag fire – van der Lubbe acting alone, or the blaze being instigated by the Nazis – allow us to view major trends in the history of Germany. The version of the Reichstag fire in which the Nazis were the culprits was a narrative developed and presented by victims of Nazism, Hett explains. The theory that van der Lubbe was the sole culprit, on the other hand, began as a self-serving perpetrators’ story. “The critical moment in the development of the single-culprit narrative—and in the Reichstag fire controversy overall—came in late 1951 or early 1952 when the Lower Saxon interior ministry ordered Fritz Tobias to research the fire in an effort to defend Lower Saxon police official (and former Nazi political police detective)Walter Zirpins”, Hett writes. It is very difficult to use victim narratives as historical sources as they are often personal accounts of people in extreme situations. As a result, victim narratives have evoked discomfort for earlier historians; only recently have these stories been examined. “It was precisely such [victim narrative] sources that tended to tell of Nazi responsibility for the Reichstag fire,” Hett notes, explaining why the single-culprit narrative has been so pervasive. Researchers are still in the very early stages of an important process of determining which accepted narratives need to be re-examined. Through much of the postwar era, Hett notes, victims have repeatedly been lost in the historiography because historians discounted their testimony, favouring ‘objective’ sources. Contemporary history is a troublesome area in particular, because it is not removed from the present. Accounts of the recent past are often intertwined with current political interests. Hett, among others, has effectively shown that accepted accounts of the past require significant scrutiny. For more information: www.journals.cambridge.org Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons user: DIREKTOR]]>

The Reichstag Fire and the Difficulties of Contemporary History