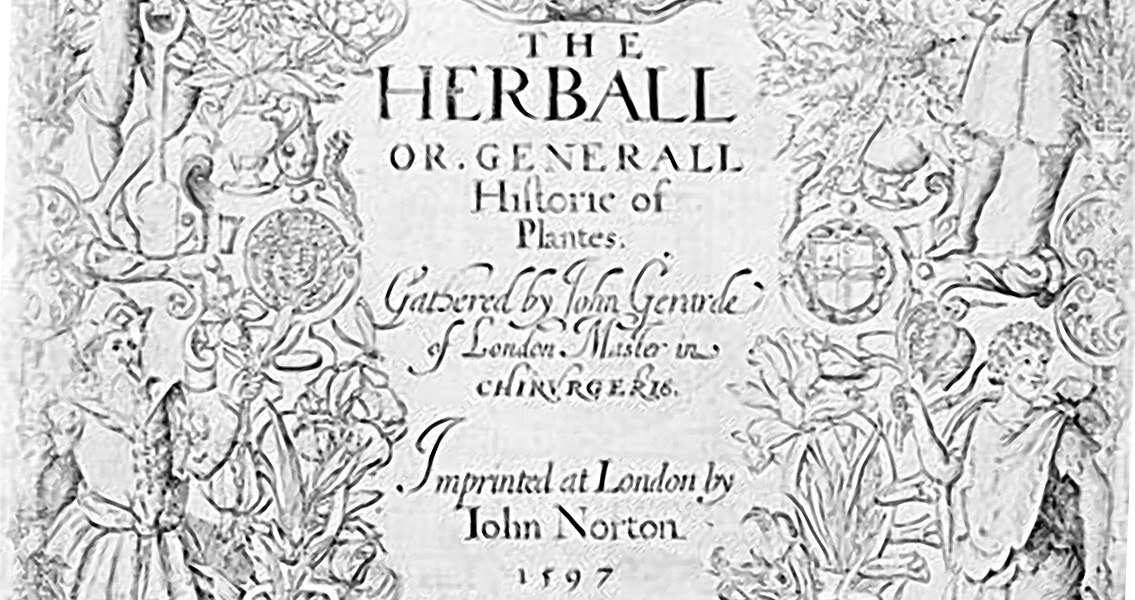

Country Life magazine, Griffiths said the identity of the man in the engraving had been coded with a set of symbols and a pattern of plants. What made the discovery possible was not just Griffiths’ knowledge of plants, but his understanding of how plants were used in a symbolic way to refer to specific individuals in sixteenth century literature. The 1,484-page ‘Herball’ came out in 1598, and was the first work of such length on botany in English. Its title page is an intricate engraving done by William Rogers, the first professional engraver in England and the best-known portrait engraver from the Tudor period. The engraving itself bears the date 1597, and features a variety of flowers and other plants, cherubs, and four human figures. Griffiths told Country Life that when he started studying the engraving he realised the patterns abounded in allusions to the people who had in some way contributed to the book, particularly four people depicted in the four corners of the engraving. Three of these individuals Griffiths identified relatively quickly. One was the engraver himself, sporting a spade in one hand and a bunch of flowers in the other. Another was Rembert Dodoens, a prominent Flemish botanist and physician, author of a number of botanical works, with a large flower in one hand and a book in the other. The third figure was Lord Burghley, the Lord Treasurer of Elizabeth I, and her closest advisor, as well as the patron of Gerard’s book. The identity of the fourth figure, however, remained a mystery at first. This figure is one of a young man with a beard and moustache, dressed in a Roman-style toga, holding a sheaf of corn in one hand and a flower in the other. The figure and the surrounding patterns suggested that this person had ”something to do with poetry”, Griffiths said. Griffiths turned his attention to these plant patterns around each of the figures, believing that they were codes for the identity of each of the four individuals. Besides the flower patterns there are also letter and figure-like symbols beneath the etchings of Lord Burghley and the man in the Roman toga. Griffiths focused his attention on the mysterious fourth figure, and after a while became convinced that, based on the information coded in the engraving, it could be none other than William Shakespeare. This, according to Griffiths, makes the portrait the first image ever discovered of the genius playwright produced in his own lifetime. The other two famous portraits of Shakespeare were made after his death. What’s more, this image, notes Griffiths, is identified as William Shakespeare by the engraver, increasing its credibility. Commenting on the discovery, Country Life’s editor Mark Hedges said it could help us see the playwright from a new perspective, that of a man highly involved with the most prominent figures of his day, a fact which could lead to new ways of looking at the sources of his inspiration. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons user: the Wellcome Trust]]>