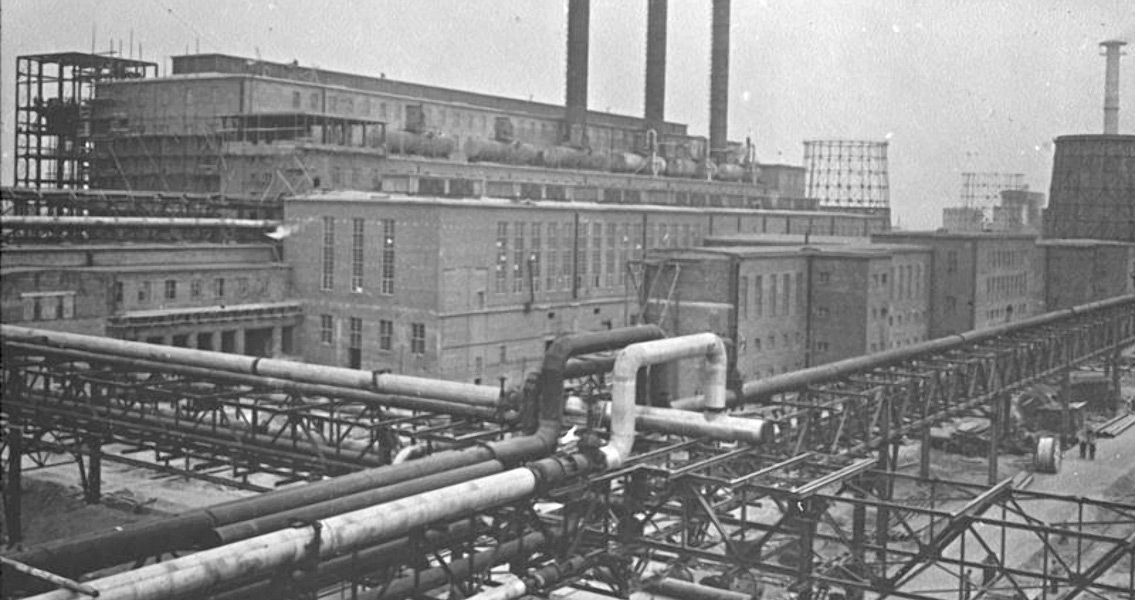

<![CDATA[Infamous for its close involvement with the Nazi war machine and some of the worst atrocities of the Holocaust, the German firm IG Farben opened a new factory close to the Auschwitz concentration camp in Nazi occupied Poland on 21st May, 1942. IG Farben was probably the most well known corporate participant in the Holocaust, and the company's history sheds a chilling light on how genocide became tied in with economics and business. Founded in Germany in 1925, the IG (Interessengemeinschaft) conglomerate quickly became the largest syndicate in Germany and the biggest chemical concern in the world, until its dissolution in 1945. The company grew out of a merger of German chemical, pharmaceutical and dye manufacturers, including BASF Aktiengesellschaft, Bayer AG and Hoechst Aktiengesellschaft. Held up as an example of Germany's ability to achieve economic self-sufficiency in the inter-War years, IG Farben had always been popular with the country's government. The election of the Nazi Party in 1933 saw IG Farben's influence grow even more. As the biggest producer of synthetic rubber, and a major producer of explosives, synthetic fuels and other vital items, the company was crucial to the economic and military ambitions of the Nazi party. IG Farben enjoyed state backing when it came to the allocation of raw materials, labour and credit. IG Farben representatives were also employed in important positions within the Nazi government. After the start of the Second World War, demand for synthetic fuels and rubber quickly started to exceed supply. It was decided to build two new plants, one of which would be located close to Auschwitz, the largest death camp in Europe. Opened in 1940, as Hitler's 'final solution' came into full effect, Auschwitz was built on a former military base in occupied southern Poland, close to the town of Krakow. Initially conceived as a detention centre for Polish citizens arrested after Germany invaded the country in 1939, the location of the camp, at the centre of the German occupied territories in Europe and close to a host of transport networks, meant it quickly expanded into something far more horrific. The IG Farben factory was situated close to Auschwitz so it could exploit Jewish slave labour in its oil and rubber production plant. In total, some 300,000 detainees from Auschwitz were employed in IG Farben's workforce, supplying the company with free labour. The company housed the workers in its own concentration camp, with the horrendous conditions there and in the factory leading to an estimated 30,000 deaths. On top of this, an unknown amount of workers deemed unfit to continue working at the factory were sent to the death camp at Auschwitz. Alongside the brutal conditions of the labour camp, IG Farben also sanctioned drug experiments on live, healthy inmates. These experiments took place at Auschwitz, but were also sanctioned at other concentration camps by IG Farben's pharmaceutical subsidiaries. Documents survive revealing a correspondence between an employee of Bayer Leverkusen (a subsidiary of IG Farben at the time) and the commander of Auschwitz, negotiating the sale of 150 female prisoners for the sake of medical experimentation. The chemical giant was so entwined in the Nazi death machine that the Zyklon B gas used in Nazi death camps was produced by another of IG Farben's subsidiaries. Following the German defeat in the Second World War, IG Farben came under the control of the Allied Powers. Several of the company's officials were convicted for the inhumane treatment of prisoners and use of slave labour. The company itself was dissolved into three separate divisions, Hoescht, Bayer, and BASF. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons user: Das Bundesarchiv]]>

IG Farben Opens Factory at Auschwitz