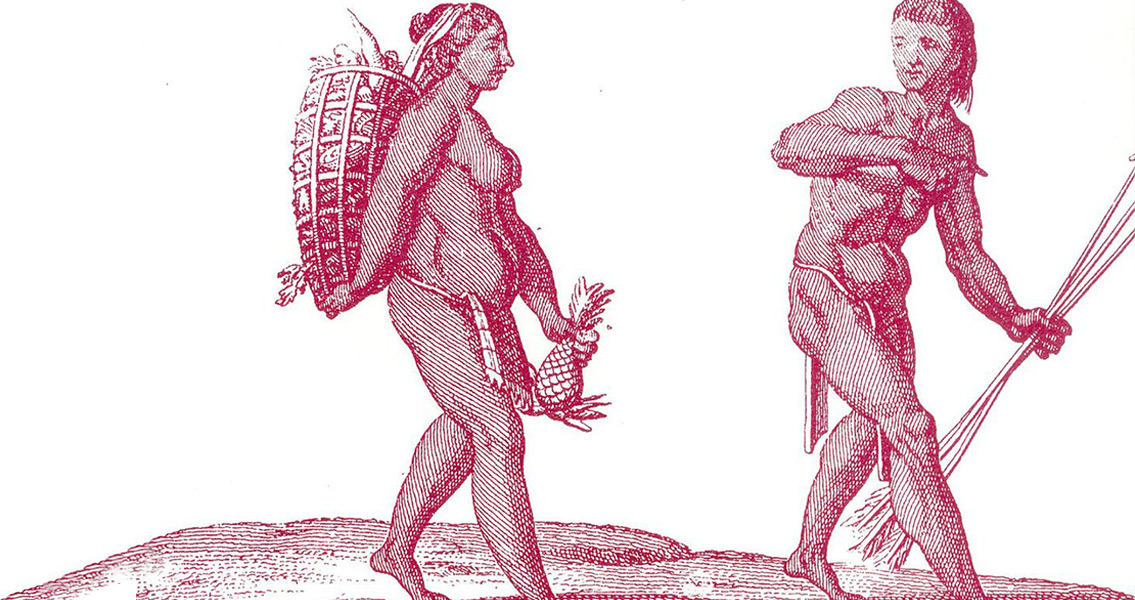

<![CDATA[A study from University College London suggests that gender equality, which we tend to perceive as a concept that has emerged in the modern era, is actually as ancient as hunter-gatherer communities. It seems, according to the research team headed by Andrea Migliano, that men and women in both ancient and modern hunter-gatherer societies have an equal say on where the group should live and how, and both genders contribute equally to the group’s wellbeing. The starting point for the team’s hypothesis was the fact that contrary to what a layperson might think, hunter-gatherer groups actually include few genetically close relatives. To see why that is, the team spent two years among hunter-gatherer populations in Congo and the Philippines, and created a genealogical database by interviewing hundreds of people from across several hunter-gatherer groups. The focus was on how they were related to the other members of the group and how often the group moved from place to place. What they found was that the average group of hunter-gatherers included twenty people, few of whom were genetically closely related, and that they changed camp at 10-day intervals on average. Paradoxically, despite this group composition, members still strongly preferred to live with their closest relatives within the group. To solve this puzzling pattern in group composition, the researchers created a simulation model and programmed three decision-making scenarios. In one, the men made all decisions when it came to group composition and travelling patterns, in another, it was the women who had the upper hand, and in a third, both genders had equal say on the matter. Somewhat surprisingly, it emerged from the simulation that only when both men and women had an equal say in questions about who should be part of the group and who should be “shooed” to another one, did the group composition end up the same as those directly observed in Congo and the Philippines. When just the men or the women had the final say, the simulated group was comprised predominantly of closely related individuals. The explanation that the research team provide is simple: gender equality gives these groups an evolutionary advantage in several respects. First, it reduces the chances of inbreeding and its often unpleasant consequences. Second, it allows group members to interact with more unrelated individuals from other groups. From this springs a number of advantages, such as the opportunity to exchange technological innovations and expand the gene pool of each group. What’s perhaps more important, is that such interactions may have been of vital importance for the development of co-operative skills in humans, the ability to work together with strangers towards a common goal, which is one of the marks of human progress. So, why did we then spend more than ten thousand years in a state of gender inequality? According to the UCL researchers, patriarchal societies formed after people started farming, settling down, and accumulating resources. In this new situation, men came to realise they could combine their resources with their next of kin to gain power and influence over their neighbours. It is possible that these familial alliances gradually led to social dominance for men and the consequent “power loss” and marginalisation of women. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons user: Pierre Barrere ]]>

Equality Helped Hunter-Gatherers Survive