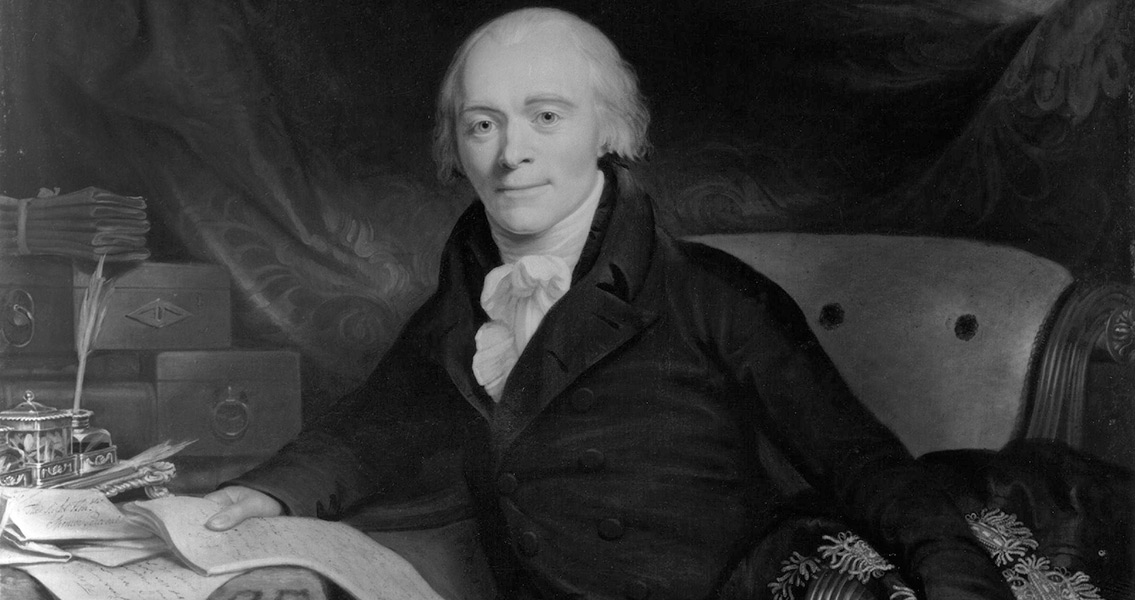

<![CDATA[11th May marks the anniversary of the death of Spencer Perceval, the only British Prime Minister to be assassinated in office. At around quarter past five, Perceval entered the lobby of the House of Commons on his way to the chamber. Sitting by the fire place was John Bellingham, a business man from London. As Perceval approached, Bellingham casually stood up, pulled out a pistol, and shot the Prime Minister in the chest. The assailant calmly walked back to the fire place and allowed himself to be arrested. Perceval is largely remembered for the nature of his death, and is often considered to have been a Prime Minister who died far too early in his term of office for him to have left a significant mark on history. However, more recent studies have reevaluated the significance of Perceval's time as Prime Minister, and the consequences of his assassination. The son of the 2nd Earl of Egmont, Perceval was born in 1762, and raised in an aristocratic family. After being educated at Harrow, and then Cambridge University, Perceval began working as a lawyer. His career in politics started in 1792, when he was elected MP for Northampton. A Tory, Perceval was a strong supporter of William Pitt's government. When Lord Portland became Prime Minister in 1807, Perceval was appointed Chancellor of the Exchequer. He built a strong relationship with the King, George III, and backed him in his opposition to Catholic Emancipation. When Portland died in 1809, Perceval accepted the King's offer to become Prime Minister. His term as Prime Minister coincided with a dramatic economic recession, and unrest among industrial workers. Perceval's government implemented stern measures against the Luddites - a group of textile workers who protested the use of technologies that reduced the need for workers in factories. One of the most significant pieces of legislation passed in Perceval's government was the Frame Breaking Act, which made the vandalism of industrial machinery a capital offence. Perceval's killer, John Bellingham, was a business man in his forties. In 1804 he had been wrongly imprisoned in Russia for fraud. The British embassy refused to aid Bellingham, and after five years in prison he had lost much of his fortune. He returned to England and applied to the British government for compensation for the money he had lost, something he felt they were morally obliged to deliver. Realising after being repeatedly turned down by the government that his plea would not be answered, Bellingham decided his only option to secure justice was to kill the Prime Minister. Tellingly, throughout his trial he repeatedly denied any attempts to declare him insane. He seemed willing to admit that his actions had been calculated and rational, rather than driven by rage or malice. He was simply doing what he felt needed to be done. He was hanged two days after Perceval's funeral. Perceval's death came at a time when Britain was embroiled in a trade war with Napoleon. The French leader's Continental System had attempted to isolate Britain from international trade, but instead led to a tense conflict which put Europe and North America's economies into recession. The Prime Minister had stuck firmly to the 'Orders of Council', his response to the Continental System, which banned trade with France for both Britain and neutral nations, to the extent that the British Navy started to board any ships destined for French territory. For many in Britain, Perceval's stubbornness was causing the devastating recession. After his death, the Orders were cancelled and the economy started to recover. This fact undoubtedly adds weight to both Perceval's time as Prime Minister, and the importance of his death. Indeed, some historians, such as Andro Linklater, and conspiracy theorists have even questioned whether Bellingham was truly acting alone in his attack on the Prime Minister, or if he was influenced by others. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons user: Dcoetzee ]]>

The Assassination of Spencer Perceval