<![CDATA[Wilson Jeremiah Moses is perhaps among the most neglected and under-appreciated historians of African American History. Appreciated by a sector of professional historians, he really deserves a more popular audience. Black History's general concern with resisting racism, engaging matters of identity, culture, and politics, can be restrictive. Focus on freedom struggles, but also repairing conquered personalities burdened and mangled, of course are of a paramount interest. Yet Moses's works does not offer proposals of how to solve these challenges nor does he side uncritically with elevating to simple heroism those who do. Instead, he challenges readers' assumptions about those deemed admirable and radical, and what the commitment to ideas by historical individuals really implies. Brilliance in the historical craft cannot be reduced narrowly to ideological and programmatic concerns nor existential resistance. Further within African American intellectual history can be found contours and frameworks which need not be seen as painfully conflicting tendencies. Appreciation of this field requires a growing awareness that people are not simply a representation of merely one idea or stereotype, whether pejorative or favorable. Rather there is creative conflict within identities and personalities, and social and individual manipulation of notions both for power but also simply as cultured fanciful expression. All contradictions in personalities and social burdens in society cannot be resolved. For a historian of ideas to suggest so is not necessarily an avoidance of responsibility or the striving for a false objectivity. When pursued with a certain depth, this endeavor can actually illuminate unexamined challenges. Moses's specialty is 19th century Black Nationalism, and he is the definitive scholar of Alexander Crummell, who was an elder mentor of W.E.B. Du Bois. But he is also a scholar of the messianic and jeremiad traditions in African American religious thought, its presence in literature and politics. Moses has an anti-authoritarian quality to much of his work, not because he has made a specific commitment to liberty or permissiveness, but because he has desired to explore African Americans identification with a prophetic or anointed leader. He has made clear contours of this tendency are not out of step with main currents in American national and theological history (and those who may wish to integrate into such visions) and Black Nationalist visions which may appear to have Afro-Asian roots. Without making a verbose fuss about the social construction of identity, what Moses has revealed, as he has surveyed diverse figures, ideas, and movements, is that a vague conception of community control of politics and economics can lead toward the same human embodying the identity of a “Black Messiah” at one historical moment, while another the “Uncle Tom,” that individual condemned as a traitor. Moses's focus has not been on condemning or elevating any one historical figure. Instead he has shown both these tendencies exist within the human character, and that students of African American History advance by alertness to this way of seeing. Growing out of this challenge, Moses begins with what is a paradox to most people. Most of the first Black Nationalists were Christians; they engaged the Greco-Roman heritage as they also searched for an African identity through Biblical “Ethiopia.” He illustrates that race men can in fact seek to be superstar individualists as they navigate the burdens of racialized writing (Frederick Douglass). Afrocentrists can also be Anglophiles or Europhiles (Alexander Crummell); the democratic and progressive minded can be authoritarian and elitist (WEB Du Bois). If pragmatists can be romantics with global visions of empowerment (Marcus Garvey); apparent idealist ascetics can be preoccupied with infinite consumption, access to money, and industrial production as the meaning of progress (Booker T Washington). The truth is most of these are human attributes and not “black” behaviors. And those tropes preoccupied with Black identity are politically interchangeable in surprising ways. Moses explains if Black anti-capitalists can have a restricted notion of equality, Black Nationalists can overstate the damage African Americans have known, suggesting an acquiescence, and a gloomy disposition toward people of color's prospects of governing themselves even in their expressions of love for their people. Both nationalists and advocates of integration have viewed Black people as God's humanizing agents or a redeemer people, proposing to repair Black people as “a nation within a nation” or placing them at the head of an aspiring ethnically plural nation that strives to be an empire. Sometimes both have been advocated intermittently. We can even witness those who lecture about self-respect and civilization building also enjoying “darky stories” and condescending to whites in power. People are known to advocate both cultural assimilation and community autonomy; Black Nationalism can be compatible with moving up certain corporate hierarchies. African American freedom movements have not always been part of counter-cultures which question authority. Some intellectual trends have even romanced the relative autonomy known under the racial segregation and subordination of the past (not for sharecroppers but a higher social class). Moses has placed these challenges within sweeping narratives which show knowledge of Jacksonian and Jeffersonian Democracy – eras distinguished by self-governing ideals marked by slavery and empire. He is alert that Social Darwinism argued for survival of the fittest and that certain cultures did not have the capacity to govern. Progressivism advocated forms of welfare and amelioration of corruption for people who might be self-reliant someday. Marxism could advocate a one party state, a welfare state, or workers' self-emancipation. These broad trends in American intellectual history tell us something essential. African American intellectual history's strains and stresses over the meanings of independence and self-reliance are not an especially troubled dilemma of Black people. But young students will not be aware of this until they strive to be competent in the ideas of American and world civilization broadly. But all of this can be misapprehended if Moses is received as someone who doesn't have an appreciation for movements for liberty and revival, and distrustful of authority in certain respects. He has a clear sense of an elevation of unity which transcends guilt and pain but also embraces the power of people to define themselves through symbols, culture, and even illusions. Moses, from his early concern with what he saw in Stokely Carmichael, as the personification of the protean store front preacher who can embody all possible viewpoints at the same time, to his interest in E. Franklin Frazier's critique of the black bourgeoisie, to his objection to the Stalinist one party state, and Ghana's Kwame Nkrumah's growing autocracy, has subtly revealed he is a close observer of social movements on a world scale for Black freedom. He even has proletarian sympathies, though these have never been extensively developed in his work. Moses has shown a sympathy toward African American young men who have a penchant for popular discourses on who is civilized and who seek some philosophical utopia but believes most instincts in this direction are not very historical. He has also shown an inclination toward middle class African American women (from the 19th century and the present) who seek to “lift as we climb” and minister to their poorer sisters whose free sexual lifestyles and children out of wed-lock disturb them while knowing this has been a divisive tact on their part. But taken together these suggest another aspect of this historian. A major thread of Moses is that he is deeply aware of the lingering 19th century legacy of white supremacy which suggested people of color were unclean, bestial, and irresponsible. That African American Christianity has promoted a type of repression which has internalized these damaging ideas, rarely inquiring what its origins are, even as the church has provided social organization. Further, that there is a fascination with power in African American Intellectual History which seeks to discipline the masses of Black people as much as liberate. In this way, Moses, is a forerunner of a critical approach to “the politics of respectability.” At the same time Moses reveals an ambivalent attitude toward moral and economic empowerment. This leaves his approach to African American Intellectual History as contradictions which cause friction within the self but that also have a vitality unresolved. His humble approach suggests that most people express a pragmatism which makes their behavior fall short of their ideals and professed beliefs. Further, that humans live with unsettled tensions that cannot always be taken up as if dialogue and debate can overcome everything. Yet he knows that popular history (the unlettered masses who are interested in history and the narratives they consume and create) have little patience for battles which appear to have no remedy. Moses's approach to history may be dismal or tragic in certain respects, but historians like political activists are not heroes, villains, or tricksters all by themselves. Glory or admiration do not come to individuals' and their ventures without anxiety or without disrupting consensus at one moment in time. A wider appreciation of Wilson Moses as historian may emerge when those who study African American Intellectual History are no longer preoccupied with vindication, that Black people are human and have their own ideas and cultures, or conversely documenting pathologies imposed by others. This is more easily said than done in a world still marked by white supremacy. Yet, this deeper discernment about Moses's work will burst forth when the means by which African Americans discipline and revere each other are seen as intimately linked to how nations, classes, and regimes claim to humanize and subordinate all at once in the modern world. But Moses, the historian, might caution us against any easy consensus, though he recognizes, with nuance, the beauty of valuing Black culture, its insights but also its illusions and myths. Recording elegantly African American Intellectual History's inconsistencies and creative conflicts have been contribution enough. Wilson Jeremiah Moses might say utopias and Afrotopias are worthy of meditation, not to be believed in to the point where anyone's real shortcomings make them “enemies of the people,” for all civilizations, even those with ideas which include jeremiads, come with discontents. For Further Reading: Wilson Jeremiah Moses. <i>Afrotopia: The Roots of African American Popular History</i>. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998. -----------------. <i>Alexander Crummell</i>. New York: Oxford UP, 1989. -----------------. <i>Black Messiahs and Uncle Toms</i>. Revised Edition. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1993. ----------------- ed. <i>Classical Black Nationalism from the American Revolution to Marcus Garvey</i>. New York: NYU Press, 1996. -----------------. <i>Creative Conflict In African American Thought</i>. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2004. ----------------- ed. <i>Destiny and Race: Sermons and Addresses of Alexander Crummell</i>. Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press,1992. ------------------. <i>The Golden Age of Black Nationalism, 1850-1925</i>. New York: Oxford, 1978. ----------------- ed. <i>Liberian Dreams: Back To Africa Narratives from the 1850s</i>. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1998. -----------------. <i>The Wings of Ethiopia</i>. Ames, IA: Iowa State University Press, 1990.]]>

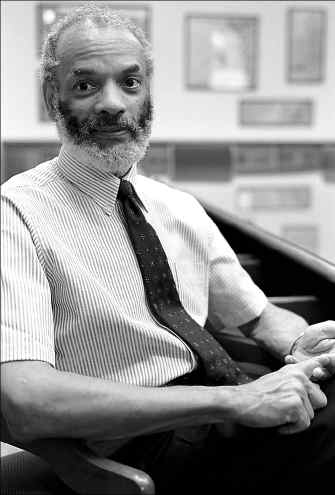

An Appreciation of Wilson Moses