<![CDATA[Much of our understanding of human evolution is based on over-simplification. We began walking upright to be able to see over tall grass, for example. Similarly, we know very little about the diet of our ancestors. The popular new Paleo Diet, for instance, encourages practitioners to return to a Stone Age diet eaten by our ancestors from 2.6 million to 10,000 years ago. It shuns modern food products such as dairy, agricultural grains and processed foods. The Paleo Diet is based on the assumption of a very specific type of 'ancestral menu'. Ken Sayers, Postdoctoral Fellow in Primate and Human Evolution at Georgia State University, has recently been conducting research in to what the ancient hominid diet actually consisted of. By studying hominid evolution from 6 to 1.6 million years ago, Sayers has revealed how our ancestors ate. Sayers notes that modern technology can be enlisted to examine ancient diets. Researchers can use the chemical makeup of fossilised dental enamel to work out the foods a hominid ate. Other researchers have focused on the small butchering marks made on animal bones by stone tools. "Such techniques are informative, but ultimately give only a hazy picture of diet", Sayers notes. "they don’t give us information about the relative importance of various foods". To understand how ancient hominids foraged, we can look to nature. So much of an organism's daily life is rooted in staying alive: finding food, avoiding predators and preparing for reproduction. Patterns of foraging behaviour among animals, may offer clues to how our ancestors foraged. Of particular interest for Sayer is which foods were particularly prized during certain seasons. A sort of 'golden rule' for foraging, Sayer says, is that when foods which are high in energy and low in handling time - so-called 'profitable foods' - are abundant, animals should feast on them. When these foods are scarce, animals should vary their diet. "Data from living organisms generally fall in line with such predictions," Sayer said. "In the Nepal Himalaya, for example, high-altitude gray langur monkeys eschew leathery mature evergreen leaves and certain types of roots and bark — all calorie-deficient and high in fibers and handling time — during most of the year. But in the barren winter, when better foodstuffs are rare or unavailable, they’ll greedily devour them." It is important to not over-simplify our ancestors' behaviours and diets. The romantic vision of an early hominid being a great hunter is probably off the mark. Running on two legs, at least before the advance of sophisticated weapons and technology, would have been a poor method for catching food, Sayer notes. The average rabbit can easily out-run the fastest human. Hominids did not spread across Africa and the entire globe simply by using one foraging method. To do so would have put early hominids at a great disadvantage. Our ancestors spread with such success because, in the words of Sayer, we were "ever so flexible, both socially and ecologically, and always searching for the greener grass (metaphorically), or riper fruit (literally)." Image courtesy of Wikimedia commons user: Alberto-g-rovi]]>

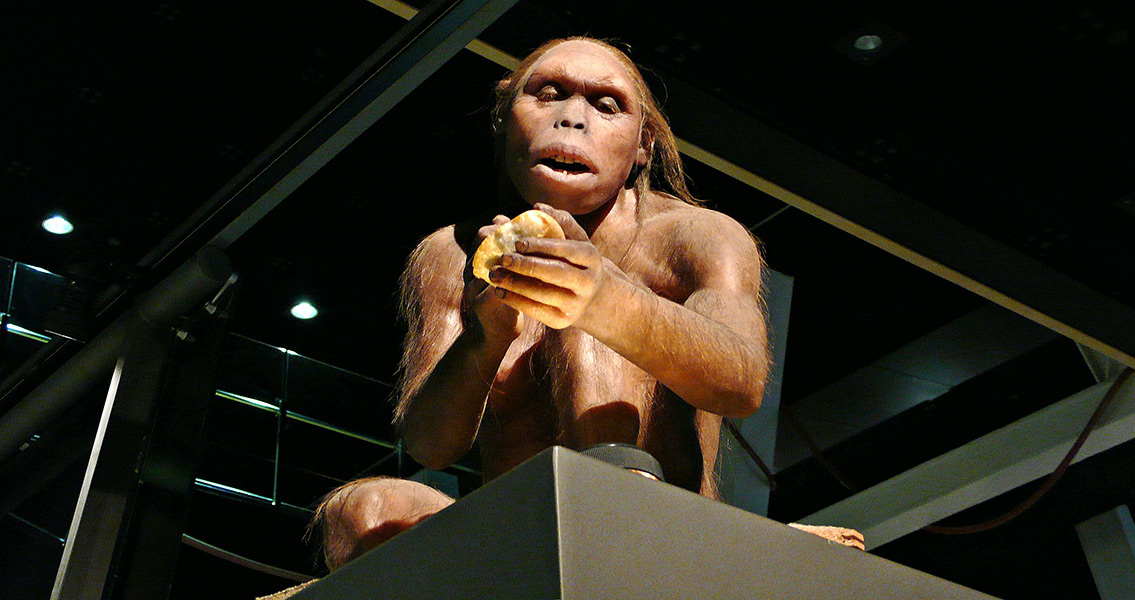

Hominid Diet was Surprisingly Varied