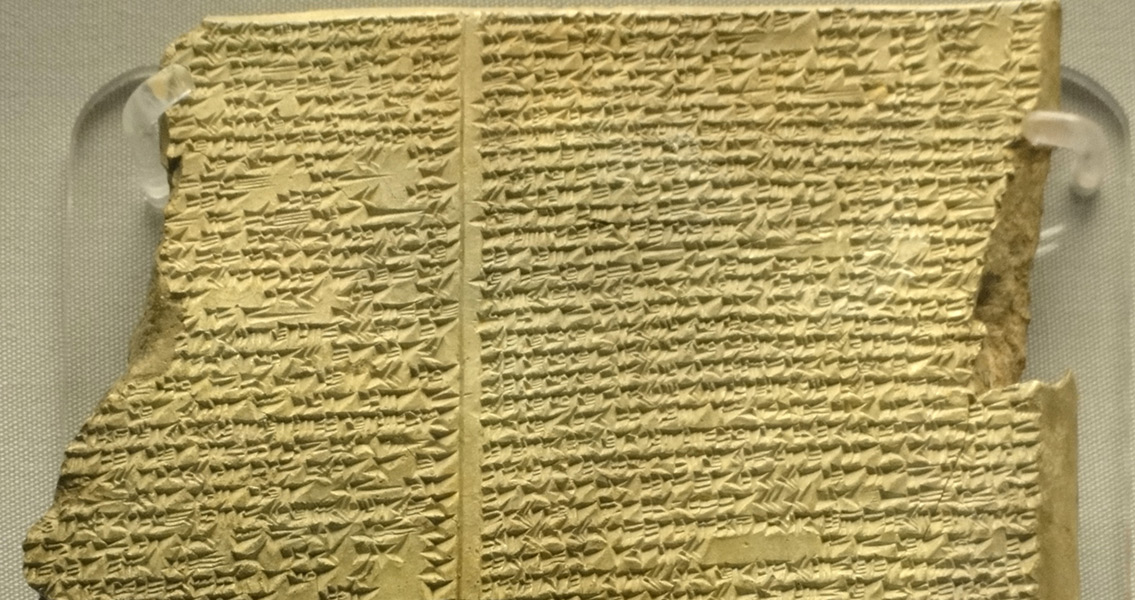

<![CDATA[A new exhibition in Jerusalem is causing heated debate. The exhibition, 'By The Rivers of Babylon', at the Bible Lands Museum, displays some spectacular examples of ancient Babylonian tablets. On show for the first time, the 2,500-year-old clay tablets written in cuneiform present artefacts from an important time in the Middle East. Experts note that the collection of 110 clay tablets provides the earliest written evidence of the Biblical exile of the Judeans in the area of modern-day Iraq. As such, the Babylonian tablets provide fresh insight into a formative period of early Judaism. Filip Vukosavovic, a curator for the exhibition, says the tablets complete a 2,500-year puzzle. Many Judeans returned to Jerusalem after the Babylonians allowed them to in 539 BCE, but some remained in the area to build a Jewish community that lasted for two millennia. "The descendants of those Jews only returned to Israel in the 1950s," Vukosavovic said. As a result, the tablets provide a unique insight into a little known period of Jewish history. Controversy has surrounded the exhibition however, as the tablets are the product of a modern, shadowy process. The recently chaotic climate in Iraq and Syria has led to the rampant theft of the area's archaeological heritage. Widespread looting has led to the international antiquities markets being stocked with cuneiform tablets. Many museums have promised not to exhibit artefacts that may have been looted, as part of an effort to discourage the illicit trade in antiquities. Cuneiform inscriptions, however, are a notable exception to this. Since 2004, cuneiform artefacts with no record of where or how they were unearthed have been allowed to be transported, in order to be examined by scholars. This is done on the condition that Iraqi authorities give their consent, and that the tablets are eventually returned to Iraq. Some argue that these precious objects, some of which are the earliest examples of writing in the world, could be forever lost if they are not looked after by conservators. "We are not interested in anything that is illegally acquired or sneaked out," said Amanda Weiss, director of the Bible Lands Museum Jerusalem. "But it is the role of a museum to protect these pieces," she added. "It's what we are here for." It has been claimed that the Islamic State extremist group and other militants are part-funding their campaigns through the illegal trafficking of historic artefacts. Trafficking and looting have, however, been going on for a long time. Archaeologists were first alerted to the problem during the first Gulf War, when Western antiquities markets were flooded with cuneiform artefacts. London-based collector David Sofer, who owns the cuneiform collection currently exhibited in the Bible Lands Museum, has denied his artefacts were trafficked. He said he had bought the tablets legally in the United States in the 1990s; and the tablets had previously been obtained from public auctions in the 1970s. The exhibition at the Bible Lands Museum allows the public to see some remarkable artefacts and to learn more about an important part of Jewish history. What must not be overlooked, however, is the damage which can be caused by illicitly-obtained artefacts. For more information: Image courtesy of Wikimedia commons user: Fæ]]>

Museum Embroiled in Looting Row