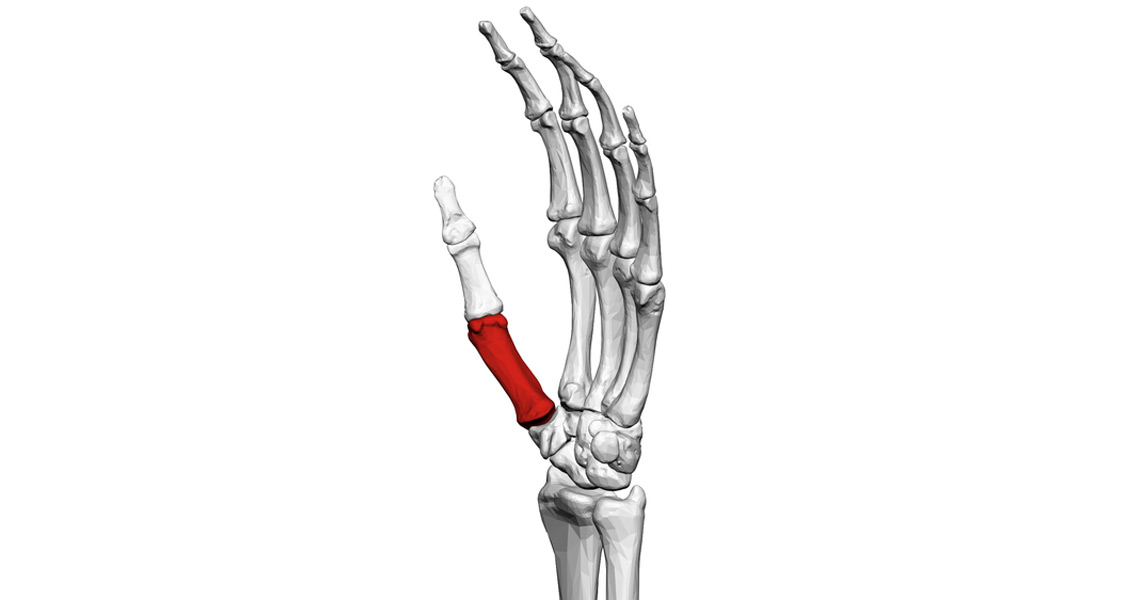

Homo sapiens, the name for modern man). By studying the bone structures of a number of hominins – the group of species that split from the chimpanzee lineage and includes modern humans and their relatives – the team were able to see how dexterity had developed in human hands. The study focused specifically on fossils of Australopithecus africanus, as well as hominin bones from the Pleistocene Period. The results could challenge the traditional ideas about human evolution. The study suggests that Australopithecus africanus were capable of having a more powerful grip than previously suspected, even though their hands lacked the styloid process. The team found that the fine mesh network of bones (trabeculae) within the metacarpals of A. africanus was comparable to that of modern humans. The density of trabeculae reveals a great deal about what a species’ hands are predominantly used for. In chimps and gorillas the mesh is denser than in humans, as chimps and gorillas use their hands to support their bodies. Less dense trabeculae however, allow greater dexterity – crucial for the creation and manipulation of tools. Kivell told Livescience: “We are suggesting that even without the full suite of humanlike morphology, early hominins were capable of forceful precision and power grips.” Chimpanzees are capable of creating and using spear-like tools for hunting. It is possible that when hominins and chimpanzees diverged between four and seven million years ago, our ancestors were already capable of creating and using tools. The earliest known tools have been found in Ethiopia, and date from 2.6 million years ago. Kivell’s research indicates that A. africanus could have been capable of using tools, 500,000 years before they were first invented. Image courtesy of Wikimedia commons user: was a bee ]]>