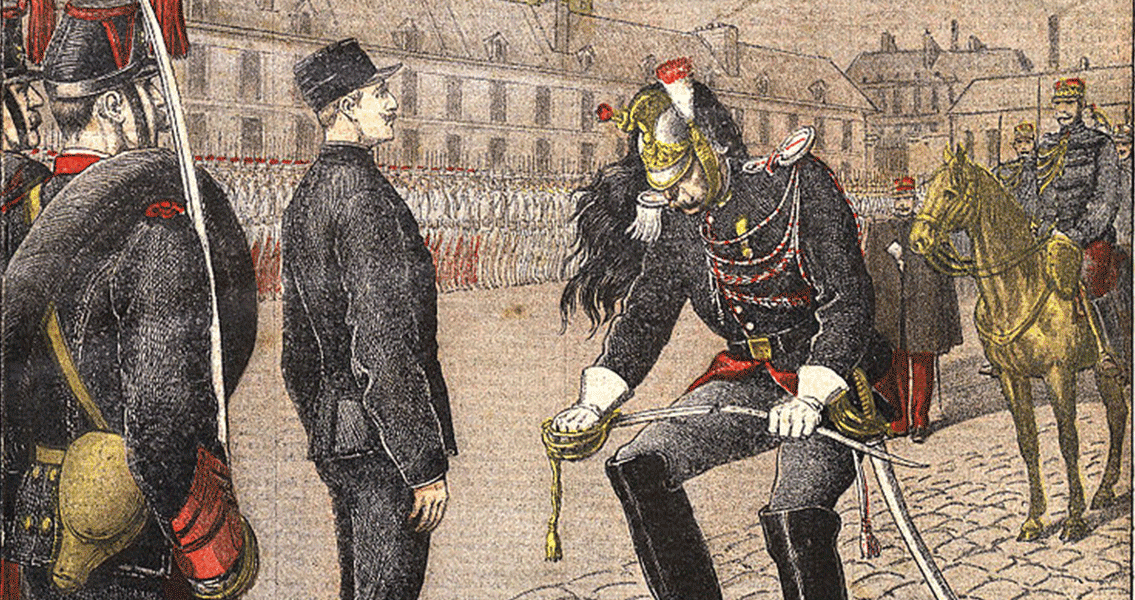

<![CDATA[On the 18th December 1900 the French government granted amnesty to anyone accused of involvement in the 'Dreyfus Affair'. By this point, the controversy surrounding the trial of Alfred Dreyfus had developed into a major scandal which revealed divisions throughout French society and publicly exposed huge levels of corruption. The Affair started in 1894 when French army captain Dreyfus was convicted of treason by a military court martial and sentenced to life in prison. The treason charge related to the accusation that he had passed on French military secrets to Germany. After his conviction, the artillery officer was sent to Devil's Island Prison in French Guyana to serve his sentence. Dreyfus defended his innocence throughout the trial and after. The trial itself was an irregular one, with the defendant prosecuted despite the evidence against him being weak and far from convincing. Historians and commentators have suggested since that the fact Dreyfus was Jewish was the biggest reason for his conviction. France, like much of Europe in this period, was a country divided along political, social and religious lines. Anti-Semitism was common throughout the country. The industrial and economic growth that occurred in the century following the French Revolution had seen the Jewish community take on an increasingly important role, either as wealthy businessmen, or in prominent positions in the judiciary, government and army. This led to resentment from French nationalists and Catholics, who viewed the Jews as damaging the French national identity, and convenient scapegoats for the social and economic problems in the country. Dreyfus' family, and his lawyer, continued to protest his innocence and fought to clear his name while he was imprisoned on Devil's Island. New facts gradually leaked out that resulted in the original case slowly unravelling. In 1896, evidence was disclosed that implicated Major Ferdinand Esterhazy as the actual guilty party. Attempts were made by the military to hide this information, but a national uproar meant that Esterhazy was court martialed in 1898 - his trial lasted an hour and saw him acquitted. In August 1898, the original letter that implicated Dreyfus - the critical piece of evidence in his conviction, was comprehensively discredited. Major Hubert Henry, the man who had supposedly found the letter, admitted he had forged it. Henry committed suicide soon after. Dreyfus was granted a retrial in 1899, and yet again the military court found him guilty, but reduced his punishment to just ten years in prison. By this point the affair had grown into a scandal, in both France and abroad. Emile Zola, at the time one of France's most celebrated writers, published a letter entitled "J'Accuse" on the front page of the Aurore newspaper (a publication owned by future French premier George Clemenceau). The inflammatory letter accused the judges at Esterhazy's trial of being under the control of the military. 200,000 copies of the paper were sold that day. Zola was sentenced to prison for libel one month later, but escaped to Britain before the sentence could be enforced. Internationally, the trial caused similar outrage. Paris was preparing to host a Universal Exposition in 1900. The event was intended to celebrate France's achievements in the late nineteenth century, and had seen the government invest in a massive construction program that included the building of two new railway stations in the capital. These plans were put into jeopardy however, as European countries and the United States threatened to boycott the Exposition due to the Dreyfus Affair. The Dreyfus Affair had divided France, between nationalists and Catholics who supported the military's position, and republicans, socialists and campaigners for religious freedom who supported Dreyfus. For those who believed the verdict should have been upheld, the campaign to free Dreyfus was damaging to France and undermining the authority of its military. For those on Dreyfus' side, the scandal and cover up revealed a dangerous, out of control armed forces that needed to be bought under the control of the government. Eventually, the French president overruled the verdict of the second trial of Dreyfus, a result of the increasingly vocal pressure to do so. In 1906 a civilian court of appeals set aside the 1899 judgment and rehabilitated Dreyfus. The event signaled a new era of French politics before the First World War, with a series of left leaning administrations working to reduce the role of church and military in government. It would take the French army until 1995 to publicly declare Dreyfus' innocence, revealing just how deeply rooted the issue had become. For France as a whole, the Dreyfus affair exposed the divisions that split the country at the turn of the twentieth century. Photo Credit: Wikimedia Commons User: Bibliothèque nationale de France]]>

The Development of the Dreyfus Affair