<![CDATA[This week marks the anniversary of the birth of one of the most infamous figures in history. The Roman Emperor Nero is generally considered to have been a brutal, psychotic and often ineffectual ruler of Rome. Although historians are now slowly starting to reassess if Nero was really as bad as some sources make out, it is clear that he presided over one of the most eventful periods in the history of the Roman Empire. Nero was born in Antium in 37 CE. His father, Cnaeus Domitius Ahenobarbus, was a descendant of one of Rome's oldest and most distinguished families. His mother, Agrippina the younger, was the daughter of Germanicus. She was exiled by Caligula to the Pontian islands when Nero was two. Soon after, Nero's father died, and his inheritance was siezed. Caligula's death meant Agrippina could return to Rome. In 49 CE she married Claudius, her uncle, and the new emperor of the Roman Empire. Nero was betrothed to Claudius' daughter, Octavia, and in 50 CE Agrippina persuaded Claudius to adopt him, making Nero the emperor's new heir. In 54 CE Claudius died (possibly poisoned by Agrippina), Nero was not yet old enough to become emperor himself, and so his mother was installed as regent to take on the role until his coming of age. It seems that Nero was reluctant to share power with anybody, including his own mother, and he quickly moved to distance her from positions of influence. By 55 CE, Agrippina's face had stopped appearing on Roman coins alongside Nero's. This was a sure sign that she had lost her position as regent, and points to the deteriorating relationship she had with her son. There are a host of different reasons offered for this collapse in their relationship; from Agrippina losing favour with her son's two most trusted advisors, Seneca and Burrus, to her siding with his wife Octavia over his affair with Poppaea Sabina. Officially, Nero told the senate that his mother was plotting to have him killed, and so he needed to act preemptively. After various failed attempts, Aggripina was eventually killed in 59 CE by an assassin sent by her own son. Nero's reign over Rome is often dismissed as something of an ineffective disaster, but there is evidence that during the first few years at least, he enjoyed a good deal of popular support. Nero publicly stated that he wanted to follow the example of one of Rome's most popular emperors, Augustus. He granted the senate greater freedom and influence. Reforms were made to laws related to public order and the treasury, and provincial governors were banned from extorting money to pay for gladiatorial shows. It has been suggested that this early stability was largely down to the ability of Burrus and Seneca to reign in Nero's most erratic tendencies, nevertheless, it's important to acknowledge that Nero's reign was not a complete catastrophe. The Great Fire of Rome in 64 CE was one of the defining moments of Nero's rule. The fire lasted six days, and according to the Roman historian Tacitus, only four of Rome's fourteen districts remained undamaged. Accounts vary on how Nero dealt with the devastating fire. Some rumours from the time claimed he watched the fire from the roof of his palace while singing, while other sources said that he actually did his best to organise the management of the disaster. The more damaging accusations came with what happened after the fire had been extinguished. Nero decided to start building a new 'Golden Palace' on one of the areas destroyed by the fire. This led to suspicion among Romans that Nero had started the fire himself, to clear the way for the palace. It is apparent that Nero knew he needed a scapegoat to blame for the devastation, and he picked a relatively new religious sect in Rome - the Christians. Many of Rome's Christians were arrested and brutally killed, making Nero the first 'Antichrist' to be proclaimed by Christianity. Such controversies continued to blight Nero's reign. Throughout the 60s military conflicts erupted throughout the empire, including Boudicca's uprising in Britain, a war with Parthia over the kingdom of Armenia, and a rebellion in Judea which ultimately saw Jerusalem seized in 70 CE. Nero's increasingly erratic behaviour, the taxation burden he was placing on the Roman people to pay for his new palace, and the unrest throughout the empire, saw the emperor's popularity diminish sharply. Governors across Europe started to renounce Nero and declare support for other candidates to be made emperor. In 68 AD an uprising against Nero saw the senate declare him a public enemy. He committed suicide on 9th June that year, rather than face execution. Even in death, Nero continued to have a profound effect on Rome, as a civil war erupted to determine his successor. It is not possible here to cover all of the events in Nero's life, for instance, the suggestion that he killed his first wife (and possibly his second), or that he left Rome for Greece to participate in the Olympic Games. It is clear however, that he is often considered a neglectful, possibly psychotic emperor, who was capable of extreme brutality. It is hard to separate fact from fiction when analysing Nero's life. Undoubtedly, the Christian Church declaring him an Antichrist means that over the centuries stories of his violent excesses may have been exaggerated. Indeed, new sources, including a recently translated poem written two centuries after his death, portray the emperor in a positive light. Whether Nero was really as bad as some accounts make him out to be, it is undeniable that he left a huge mark on the history of Rome.]]>

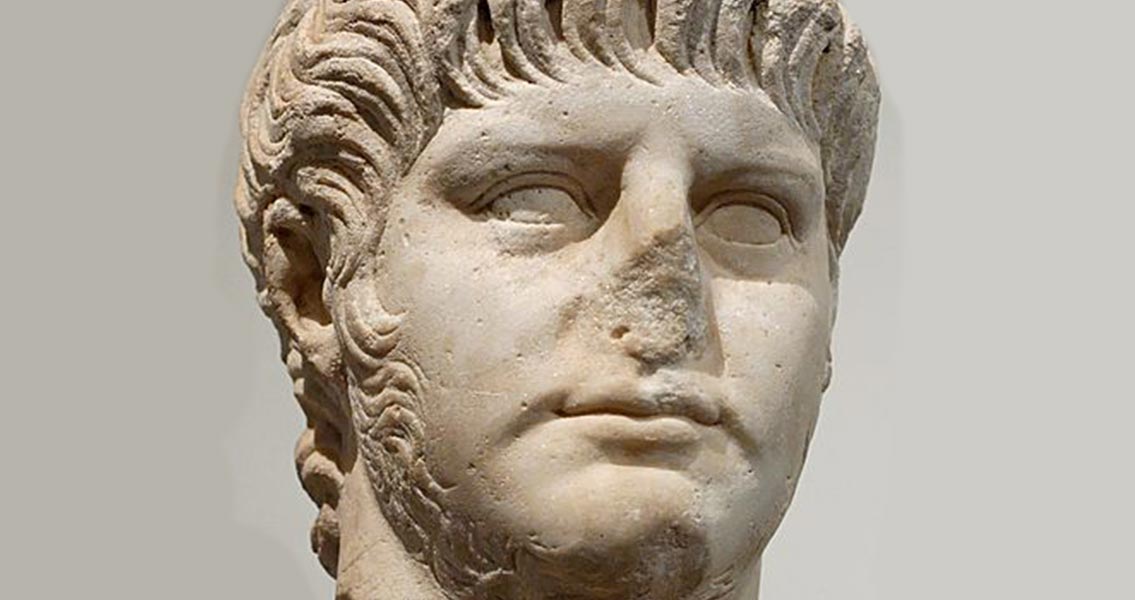

Nero