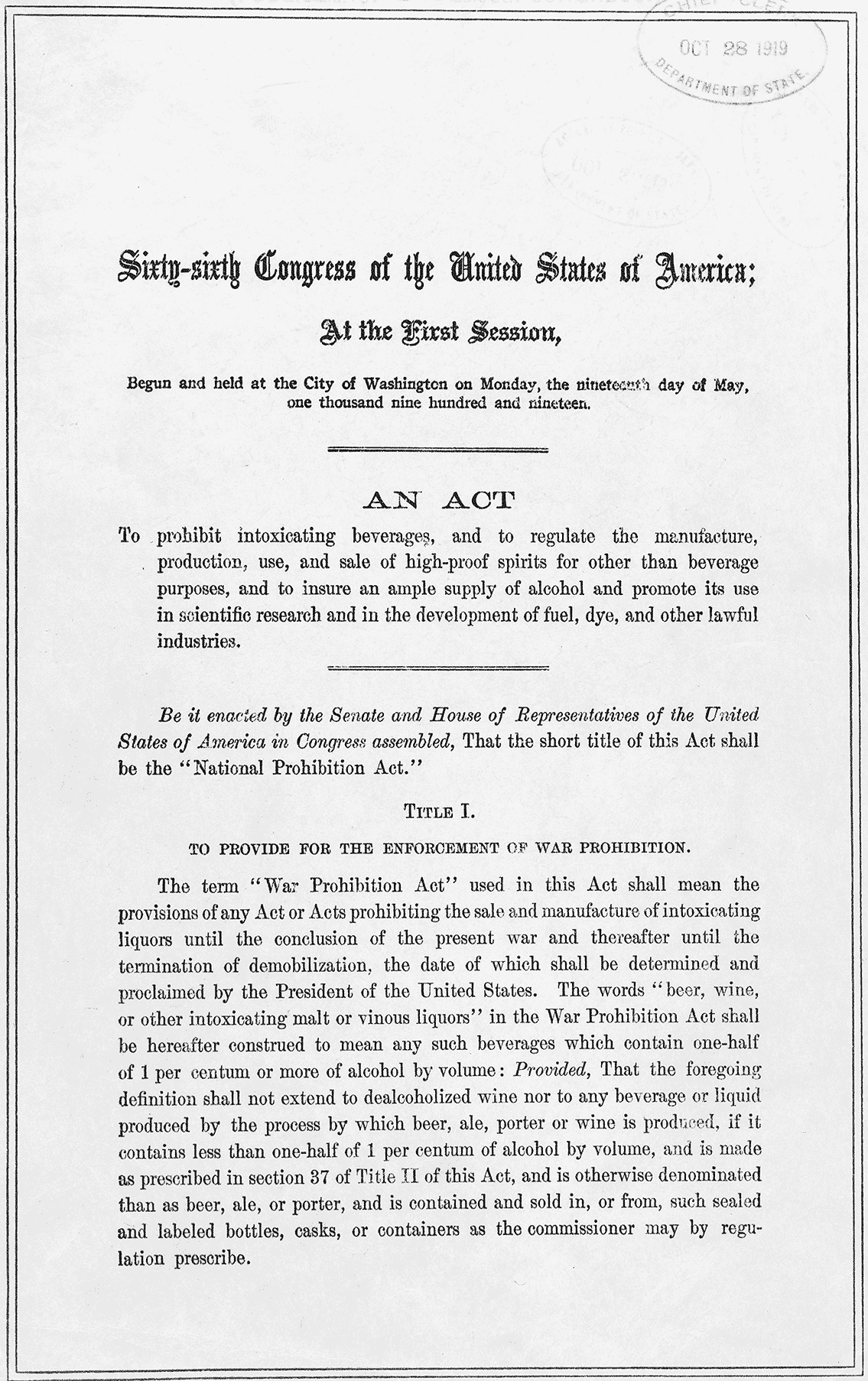

<![CDATA[On the 28th October 1919, the National Prohibition Act was passed in the United States Congress. The new law was popularly called the Volstead Act, after Congressman Andrew J. Volstead, chair of the Senate Judiciary Committee that sponsored it. The Volstead Act was a piece of companion legislation to the 18th Amendment, which prohibited the manufacture, sale or transportation of 'intoxicating liquors' in the USA. Woodrow Wilson first instituted a temporary prohibition on alcohol in 1917, as a consequence of the United States' entry into the First World War. Although prohibition campaigners throughout history had tended to focus on religious and moral arguments for reform, the temporary measure was installed for purely practical purposes, at least initially. As US resources became stretched by war, it was decided to stop the manufacture of alcohol to preserve grain resources for food. Later that year Congress submitted the 18th Amendment for ratification, which was completed in just eleven months. The National Prohibition Act gave form and structure to this ban, in anticipation of its eventual implementation in 1920. It laid out definitions for what constituted intoxicating liquor, established the penalties for violating the act and installed procedures for its enforcement. The Temperance Movement had a long history in the United States prior to the 18th Amendment. It had its origins in the burgeoning trend for grassroots religious revivalism and moral activism in the 1820s and 1830s, and originated around the same time and from a similar context as the movement to abolish slavery. Broad justifications for the Temperance Movement came from the beliefs that alcohol was damaging to American society and family life and against God's will. In 1838 Massachusetts passed a law banning the sale of spirits in quantities less than fifteen gallons, and in 1846 Maine passed the first state prohibition law. These would prove the precursors for the later federal legislation. Prohibition came into effect in January 1920. From this date, it was illegal to drink liquor in one's own home, or as a guest in someone else's. Americans could no longer carry a hip flask or give and receive liquor as a gift. Bars, restaurants and hotels could no longer sell alcohol, and it was illegal to bring alcohol from outside and consume it at these places. Popular demand continued despite the strict laws and risk of punishment and the means of evading the authorities ended up creating more disruption to society than alcohol ever could. Ordinary people found innovative loopholes that allowed them to produce their own alcohol. Beer manufacturers sold 'wort,' beer that had been removed from the manufacturing process before alcohol could be added. The buyer could then take it home, add yeast, and wait for the alcohol to ferment. This evaded punishment as the producer was not making alcoholic beverages, and the consumer wasn't buying them. Speakeasies cropped up, especially in the major cities, these were bars or shops where alcohol could be bought and consumed in secret. Both seller and customer benefitted from keeping the speakeasies hidden from authorities, and worked together to keep the places concealed. Speakeasies and homemade beer were of course troubling to authorities and difficult to police, but the most startling and dangerous development was the rise in organised crime to meet the sustained demand for alcohol. Notorious gangsters such as Al Capone made fortunes bootlegging alcohol, a fortune that was being taken away from the formal economy and given to the black market. A criminal underworld formed in major cities, reaching its bloody climax with the St. Valentines Day Massacre in Chicago in 1929, a brutal event that highlighted the growing lawlessness between rival gangs. The years of prohibition had created an enormous criminal underworld, for which there were simply not enough law enforcement officers to police. As the 1920s wore on, support for prohibition continued to decrease, and Repeal Movements began to crop up around the country. On top of this, as the Great Depression took hold in the 1930s, a return of the liquor industry out of criminal hands was viewed as an effective way to generate income and jobs. Franklin D. Roosevelt included the repeal of prohibition as a key element in his election campaign in 1932, and his landslide victory set the United States on the path to drinking again. Prohibition was often referred to as the 'noble experiment'. Lasting more than a decade, its eventual failure proved that good intentions would not over turn popular demand. Depriving people of something they craved without effectively policing the ban would simply lead to criminality, not a reformed society.]]>

The Volstead Act – Formalising the Noble Experiment