<![CDATA[On the 6th October 1945, one of the most controversial figures in French history tried to take his life in an attempt to pre-empt his impending execution. Pierre Laval has come to embody an ugly part of French history. Defeat to and occupation by Nazi Germany was of course a disaster, but the Vichy government's collaboration is a controversy that France is still coming to terms with. Since the end of the war, the history of France in World War Two is constantly being rewritten, as new evidence on the balance of collaboration and resistance comes to light. Laval had received the death sentence for treason. He was scheduled to be executed by firing squad on the 6th October. His failed suicide bid that morning postponed his death for just under two weeks. He had swallowed deadly cyanide pills as he waited for the arrival of his executioners. A doctor managed to save his life, so he could face his punishment. Laval had insisted throughout his trial that he had done nothing wrong during the Nazi occupation. As the war was coming to a close and an Axis defeat seemed more and more inevitable however, he had fled to Germany, Spain, and finally Austria, where he was captured by Allied forces. He may have claimed to have done nothing wrong, but his flee seemed to suggest he knew punishment was coming. When Henri Petain took control of the Vichy Government following the signing of an armistice with Germany in June 1940, Laval was awarded the post of deputy head of state and foreign minister. Although officially government for the whole of France, the Vichy regime only really controlled the south as the north was under German occupation. When the Allied forces landed in North Africa in November 1942, Nazi forces moved to the south of France to defend it against attack, and the Vichy government was reduced to nothing more than a puppet of the German forces throughout the country. Since France's liberation, historians have long debated the extent to which the Vichy government was making the best of a bad situation, and to what extent it was actively collaborating with the German forces. Laval sits right in the centre of this dilemma. In December 1940 Petain removed Laval from office because he had been holding secret negotiations to formalise a Franco-German alliance. The Nazis successfully pressured Petain into reinstating him. By 1942 Laval was made head of Vichy France after Petain fell further from grace. Laval would quickly begin taking away rights from French Jews, and organising the round up and deportation of non-French Jews. He made public announcements in support of the Nazi's in the fight with the Allies. He seemed desperate to reassure the German forces in Berlin of his loyalty. Whether this was for his personal gain, or out of a genuine belief it would save the French people from the wrath of the Nazi occupiers, we will never know. Another policy that highlights the ambiguity over Laval's position is the means by which he tried to secure the return of French prisoners of war. Laval brokered a deal with the Nazis for three native French workers to be sent to work in Germany in exchange for the return of one POW to France. Such a deal seems unthinkable now - using the citizen's of one's own country as a bargaining chip, while voluntarily strengthening the war machine of an occupier. On the other hand, we was negotiating the safe return of French soldiers, surely a popular cause, while those sent to Germany would only have to give their labour. As the Nazi defeat became a foregone conclusion, Laval attempted to reform the French National Assembly in the hope of returning a French government to the country. This move would see him arrested by Nazi forces, although he managed to quickly make his escape. Again questions are raised about Laval's motives. Was this him seizing the opportunity to return power to the French people, or was he calculatedly trying to switch allegiances with the changing tide of the war? Laval left a note at his attempted suicide, which read "To my advocates - for their information: to my executioners - for their shame. I refuse to be killed by French bullets. I will not make French soldiers accomplices in a judicial murder." He seemed to believe he was being made a scapegoat for the events of the German Occupation. Laval's life is an extreme personification of the complicated politics that occurred in occupied France. The motives behind his actions will never be revealed, but his story stands as the embodiment of a controversial part of French history. ]]>

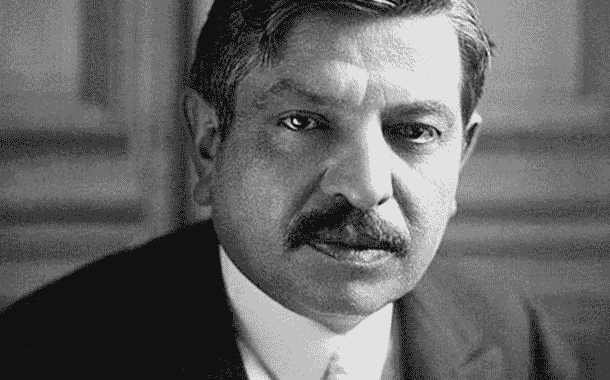

Pierre Laval – Collaborator, Opportunist or Realist?