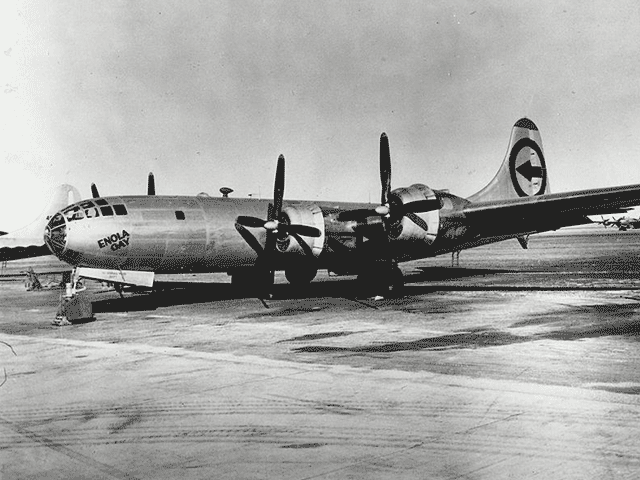

<![CDATA[“It was hard, hard work. We had been training for several months for the mission and we knew it was going to be different, and we had to do it properly.” Theodore Van Kirk, the last surviving member of the crew who dropped the first atomic bomb on Hiroshima, has passed away. Van Kirk was the navigator on the B-29 Superfortress ‘Enola Gay.’ He died in Georgia, USA, at the age of ninety three. Van Kirk’s death serves as a poignant reminder of the horrific brutality of conflict and the morally questionable tactics used by both sides in World War Two. Most importantly it reminds us of the human experience of war. His death, alongside being a personal tragedy for his friends and family, also signifies an increasing detachment between us and our past, as the connections with the last ‘total war’ become ever wider. The Enola Gay set off from Tinian, a Pacific Island, on the 6th August 1945, escorted by two other B-29s. Descriptions of the plane taking off reveal an atmosphere of fanfare. The runway was lit up by floodlights, because the Manhattan Project’s leader General Leslie R. Groves wanted the event recorded for posterity. Photographers covered the runway and Colonel Paul Tibbets, the plane’s pilot, was asked to wave for cameras before take off. These descriptions seem almost unbelievable for the prologue to an event that would have such devastating ramifications, and tell us a great deal about attitudes leading up to the first deployment of an atomic bomb. By 6th August, Germany had already surrendered to the Allies. Japan was for all intents and purposes losing the war in the Pacific region. The American war machine was at full power and had recovered from the shock of Pearl Harbour four years earlier. Great inroads were being made into Japanese territory, but there seemed little chance of the country surrendering. A costly, bloody land war on Japanese soil was beginning to seem more likely. Although the reasons why President Truman authorised the dropping of the bomb are incredibly complicated, the desire to save the lives of U.S. soldiers by ending the war quickly was surely a key consideration. Such a calculation seems incredible now- a case of deciding between the lesser of two unthinkable evils. Others have argued that the dropping of the bomb was a means to announce America’s might to the world, and particularly to the Soviet Union. One could argue that the moment the Enola Gay dropped its payload the Second World War started to close and the Cold War began. It was the point where existing tensions began to explode, and the nuclear arms race between the two nations started in earnest. Van Kirk was only twenty four years old when he flew his most significant mission. It seems an incredibly young age to cope with such huge responsibility. In an interview with Spiegel in 2005, he mentioned that although he was not “proud” of the deaths caused by the dropping of the bomb, he could not think of any other way of ending the war. He went on to say “I think people that go around and start wars for any reason whatsoever are crazy, but that's another story.” The recollections of people like Van Kirk connect us to a past that is increasingly unimaginable. The historical significance of Hiroshima in terms of the Second World War and the nuclear age will always be studied and debated, but the experiences of the participants seem increasingly distant. Kurt Vonnegut referred to World War Two as the ‘Children’s War’, alluding to not only the youthfulness of many of its participants, but the completely alien reality that enveloped so many lives. With the passing of people like Van Kirk, there is a danger we will further lose contact with the human experience of a past that even now seems more and more unbelievable.]]>

Last Crew Member of the Enola Gay Passes Away