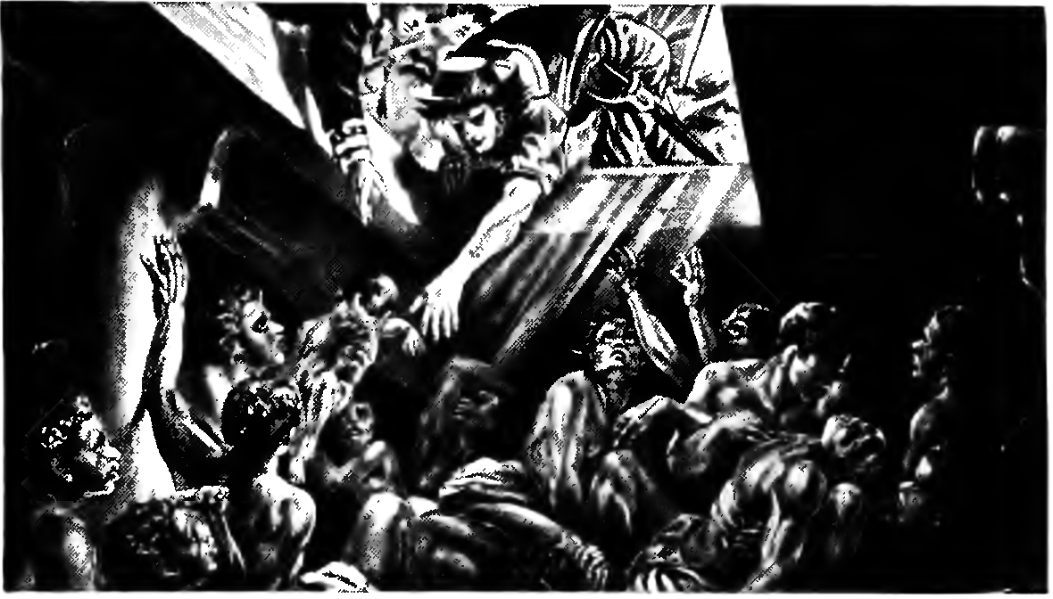

<![CDATA[The Hartford Courant recently finished a year long investigation to study the logbooks of an 18th century ship that ended up linking New London ships to the West African slave trade. According to this logbook, men from Connecticut travelled to Sierra Leone, where they bought slaves to be shipped as slaves to the West Indies. Contrary to popular belief, the keeper of this logbook wasn’t Sam Gould, but an aristocrat named Dudley Saltonstall. Ever since this discovery was made about 10 years ago, researchers have continued their studies on the slave trade and the involvement of North London families in the slave trade. A number of details have emerged since the first revelations and more and more ships have been linked with the slave trade. In fact, some of the leading families of the colonies were also said to be involved with slave trade. The suffering of captives during the Middle Passage from Africa to the Caribbean has been well documented. However, the logbooks and ongoing research highlight the lethal nature of the trade – both for the officers as well as the seamen. According to records, traders from Connecticut had died of fevers, killed in uprisings or been mutilated at the hands of black traders. One particular captain had his head bashed in by his chief mate, a crime to which the chief mate later confessed. Saltonstall was just about 18 when he first began to maintain a logbook in the voyage of 1757. His father, Gurdon Saltonstall, was the deputy mayor of New London and an extremely successful merchant as well. According to reports, Gurdon owned two of the three ships for which young Dudley kept records and logbooks. It also appears that Gurdon placed Dudley on the ship so that he could monitor the distributions that were being distributed to the seamen and act as his father’s eyes and ears on board the ships. According to Saltonstall’s log, the ships were in Sierra Leone on April 8, 1757 so that the seamen could buy rice to feed the slaves. The logbook also recorded that the ships were at Bence Island to take in slaves, wood and water five days later. Further proof was found when a record dated April 27, 1757 stated that 169 slaves had been boarded onto the ships. However, numerous slaves on board Dudley Saltonstall’s ship became infected with amoebic dysentery and began to fall ill during the first week itself. The logbook states that one slave fell dangerously ill and another slave died on May 4, 1757. Yet another post for the very next date mentioned that 3 more small slaves had died from the flux within a period of 24 hours. Another entry dated May 14 stated that a total of 9 slaves had died, leaving a total of 160 slaves on board. Dudley Saltonstall might have been court martialled for the loss of 100 ships and the rout of the Colonials in Maine’s Penobscot Bay, but he still managed to always land on his feet. He was disliked by his officers and was known to be extremely snobbish and arrogant. Later on in the war, Saltonstall brought the greatest prize ship of the war – the vessel that belonged to the British General Sir Henry Clinton. However, this achievement did not erase the massive costs that were spent in the Penobscot Expedition, a Pearl Harbor equivalent during the Revolutionary War. It is believed that Saltonstall remained in the business till almost 1784, traces of which were found in letters written to his wife where he mentioned that he longed to buy 300 slaves in order to sell them off in Charleston, S.C. ]]>

Logbooks Show Proof of Death and Misery Onboard Connecticut Ships