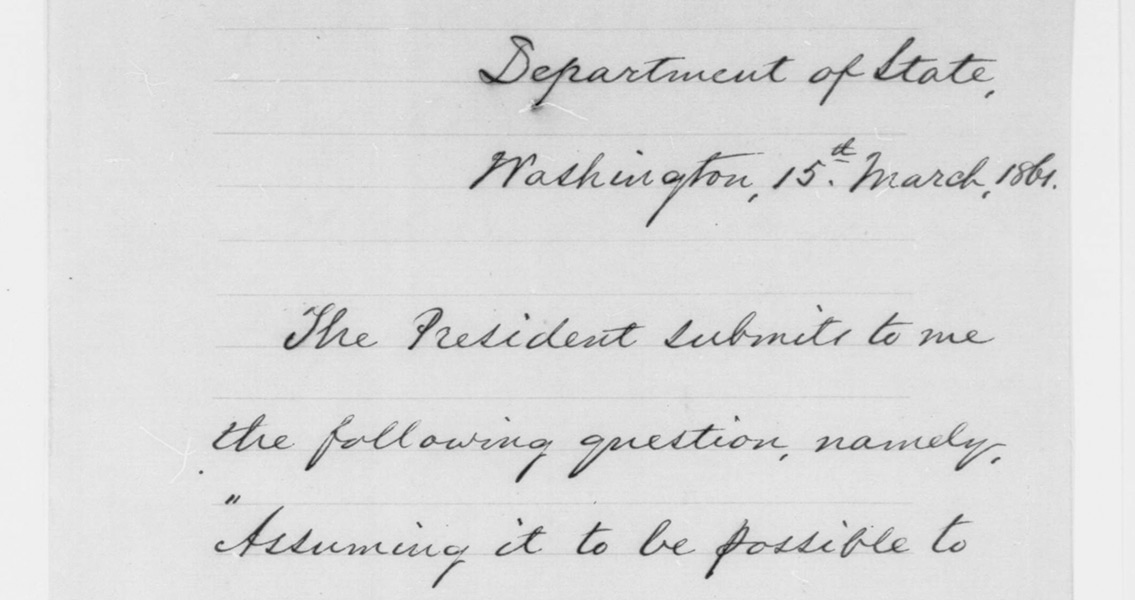

L.A. Times regarding the cache of documents and 35 leather-bound ledgers related to telegrams that were sent between 1862 and 1867. “We don’t really know what is in here. Every single telegram has a story behind it, from the president to the greatest generals and to the privates and telegraph operators. It’s like putting together a huge jigsaw puzzle.” The telegrams were kept by Thomas T. Eckert: head of the U.S. military telegraph office at the War Department and a Lincoln confidant. The Huntington has begun a Decoding the Civil War crowdsourcing campaign relying on volunteers to unravel secret texts using cipher charts. So far, over 2,100 “citizen archivists” and war buffs around the world have been able to transcribe less than a third of the collection. The project still has an open invitation for volunteers. The telegrams cover the gamut; from heartbreak, sarcasm, warning and conniving to draft riots, downed cables and cotton markets. They also include the latest news from the battlefield, like Lincoln’s venturing that Grant’s forces had “Petersburg completely enveloped” and had captured “about twelve thousand prisoners & fifty guns.” In a telegram about troop movements, Gen. William T. Sherman reflects sorrow: “my eldest boy Willie, my California boy, nine years old died here yesterday of fever and dysentery contracted at Vicksburg. His loss to me is more than words can express.” Some are less serious, like the telegraph sent by J.W. Carver that informs Eckert: “Family matters require my immediate attention at home for a few days. If not attended to at once I am utterly destroyed.” The messages, tapped out by around 1,500 telegraph operators, traveled over approximately 15,000 miles of telegraph lines and revolutionized wartime communications. Eckert, who would go on to become president of Western Union, took the telegram ledgers when he retired in 1867. Until he died in 1910, the documents were left in storage. In 2008 they surfaced and were subsequently sold at auction for $36,600 to a company that specializes in rare books, the William Reese Co. The collection was sold to the Huntington in 2012. “The telegrams were actually considered lost,” Mario Einaudi, who is overseeing the project to digitize the documents on behalf of the Huntington Library, told the L.A. Times, “They’re significant in that what we’re making available to people is raw history. The language comes through so loud and clear that it puts you back on your heels.” ]]>